How Joe Willie Namath Saved Football from Itself and Changed a Nation Forever

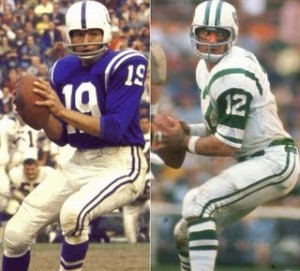

Johnny Unitas and Joe Namath each personified an era in Pro Football history.

“I Can’t Wait Until Tomorrow…’Cause I Get Better Looking Every Day“…words to live by.

I was a 10-year-old farm boy when Joe Namath signed the biggest contract in pro football history.

The war between the AFL and NFL had reached its apex, and the news of Namath’s choosing the upstart AFL traveled far and wide—even to our local weekly, the little ol’ “Reidsville Review” down in Carolina.

At that point in my life, my knowledge of professional football was gleaned from family gatherings around a huge woodstove on Sundays and an occasional peek at a snowy black and white TV that the men huddled around after church…as long as I was quiet.

Out of those bull sessions, I surmised that Johnny Unitas and the Baltimore Colts were, and always would be, the greatest group of athletes in the history of the game…forever, 1958’s “Greatest Game Ever Played” being the benchmark against all who would challenge their superiority.

Six months later, my father uprooted us and followed his company north to the Dalmarva peninsula and the heart of Colts country. We left behind the red clay tobacco fields, the mule and milk cows, and moved into a suburban life of middle-class America.

Six months later, my father uprooted us and followed his company north to the Dalmarva peninsula and the heart of Colts country. We left behind the red clay tobacco fields, the mule and milk cows, and moved into a suburban life of middle-class America.

Instead of biking the graveled back roads with the same three friends for hours on end, I was shoved into a group of 100 or so children of the suburbanite culture, crazy about sports and crazy about heroes.

The one constant was…the Baltimore Colts…but I kept watch out of the corner of my eye on this AFL deal and this guy, this incredibly cocky No. 12 of the Jets.

By the close of 1965, the official escalation of the second Indochina war was almost 12 months old, and we were losing an average of 155 22-year-old men per month—1,863 officially for the year. The nation cringed and the seeds of doubt were planted.

That year, a street busker from Berkeley by the name of Joseph Allen McDonald penned the now infamous “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-To-Die Rag” and the infant “counter-culture” had its anthem.

The AFL had finagled a lucrative contract with ABC to televise it’s games nationwide and our move north meant no more fuzzy black and white games fighting their way from Raleigh-Durham, but a choice of games from Philadelphia or Baltimore…in freakin’ COLOR.

That’s what sold me on the AFL. They had flashier uniforms, they threw the ball…a lot…and there was that tall, lanky dude from Beaver Falls, PA who was not only playing football with abandon, he was living the high-life that every man-child dreamed of.

He was “Broadway Joe” now or “Joe Willie” as Cosell called him.

There was the Fu Manchu, a mustache wasn’t enough, it had to be a “spectacular” mustache, there were the white shoes, so easy to find in a sea of black high tops, the mink coat on the sideline. It all screamed “Individuality” in a world of Madison Avenue conformity.

Still, there was a war coming into our living room every night—a war brought to you by Gillette, DOW Chemical, and Chevrolet; a war sanctioned, blessed and sponsored by the ‘establishment’—a war that ended up erasing almost 60,000 members of my generation.

As my family stood the last goal-line defense for the great ’50s American Dream…I hooked it wide left.

By 1968, my freshman year of high school, I was no longer that little country bumpkin from Rockingham County. I had grown to a 6’0″, 215-pound wannabe quarterback on the famous late ’60s Middletown, DE Cavalier JV squad.

I played center. I played fullback. I played tight end…I played none of them well. Perhaps as a consolation, perhaps only because it fit, I was issued the No. 10. I wanted No. 19…or No. 12.

I was forever resigned to ‘lineman eligible’ status…and I blew that, too.

In a season and a half, I created more chaos in that locker room than Bill Billings had ever seen. Beer, long hair, girls, drag racing, joy rides in the town police car, all under the radar and hidden from public view…the coaching staff put up with all of that and more because I was big and could long snap like a QB.

What straw broke the camel’s back?

Those white shoes…I wore white shoes to a pregame scrimmage one day. I crossed that unseen line in the sand between the past and the future and I had unknowingly slipped into the evil counter-culture that had infected this great nation in her time of crisis.

On the field, the royal blue and white Middletown Cavaliers were the spittin’ image of the Baltimore Colts minus the horseshoe, even down to the black hightops we were required to wear. White shoes weren’t part of that image. I had made my last snap.

Thank you, Joe Willie Namath.

1968 was a year of transition as well for this country and for the New York Jets. The war had turned bad by then and it’s various opponents had finally united to stop the slaughter.

After the Tet Offensive exposed the strategic weakness of America’s base defense systems, the U.S. military indiscriminately bombed, burned and destroyed anything it viewed as a threat to South Vietnam’s security and the phrase “We had to destroy the village to save it.” entered the American lexicon.

This nation was torn apart, and I rolled with it.

The NFL was the “establishment” as were my beloved Colts. The AFL were “counter-culture” all the way.

No more “three yards and a cloud of dust”, Namath had thrown for 4,007 yards in 14 games, Joe Willie had made Don Maynard and George Sauer household names in 1967.

Namath had taken the Jets from a football joke to championship contenders in three short seasons.

With this nation in flames and our government in paranoid denial, racial tensions spilled onto the front page, and the population poised to split along generational, racial and political lines, we needed a hero, someone who could do battle with the status quo.

With the “establishment” maintaining control in a manner that would shame the KGB…the “other” America needed someone cool, someone young, brash and willing to tell the NFL “establishment” to “stick it.”

We found that hero in Joe Namath.

The details of Namath’s war with the league and his proclivity for the spotlight are well chronicled and need not be rehashed ad nauseam.

He stood his ground, the league submitted, a compromise was reached and the league thrived because of it. If this handsome gunslinger had anything on his side it was the destiny to evolve and control his environment.

On that humid, overcast day in Miami, Namath evolved, he tossed aside his gunslinger ways and took the game to my Colts on their terms…and won.

Joe Namath beat the “establishment” with their own weapons…a solid run game, timely throws and clock management.

Something died in me that day in Miami…but in every death there is a re-birth. The Colts and my boyhood icon had aged before my very eyes but my faith in social change and it’s righteousness was re-born that day as well. I don’t think I’ve ever given up hope since.

In a precursor to American history, the leagues merged and became one of the most successful capitalistic ventures in history, it became the flagship “establishment” enterprise and Joe Namath, his outrageous contract and his legitimizing his own personal ‘counter culture’ made that happen.

It took a few more years for the American “counter culture” and “establishment” to merge, to kiss and make up if you will. A war had to end, veterans had to rejoin the mainstream sans guilt and mothers had to bury their 58,913 children once and for all.

As the AFL and NFL recognized that their “war” was self-defeating, eventually so did we as a nation.

By the time I mustered out of the Infantry in 1975, the nation seemed to be back on track…and Joe Willie became just another bad kneed quarterback with a porous offensive line. The nation had begun to heal, if not Joe Willie’s knees.

Namath passed from our view as his career and the war wound down. His star shown bright and blew by us in a quick blaze of glory. It was our loss, Joe. It was our loss.

It took two extra years to see him elected to Canton, but in the end, the old “establishment” and new “counter-culture” Hall of Fame voters hugged and got it right, embracing Namath not for the numbers, the white shoes or the mink coat, but for the impact he had on the NFL and a nation at it’s height of crisis.

*For a further, more comprehensive discussion of Joe Namath’s place in American history I leave you with Rob Kirkpatrick’s “1969: The Year Everything Changed”

(dedicated to Lisa Horne)

We are a gaggle of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our community. Your site offered us with useful info to work on. You have done an impressive process and our whole group might be thankful to you.

Hey There. I discovered your weblog the use of msn. That is a very smartly written article. I will be sure to bookmark it and return to learn more of your useful information. Thank you for the post. I will certainly comeback.

This really is similarly a great content material we very truly loved looking at. This is not constantly that we have possible to sort out a problem.Zorgverzekeringen Vergelijken