Remembering Jesse Owens: An American Hero

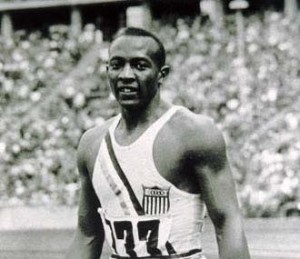

Jesse Owens became an American hero at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin.

Perhaps you have heard of Jesse Owens. Back in 1936, he won four gold medals at the Berlin Olympics, becoming the first American to do so.

Not only did he become the first American to accomplish this feat, he also sent a loud message to Adolph Hitler and his ideology.

Hitler was convinced that the white race (Aryan) was superior to all others. This became all too evident in the horrifying discoveries of concentration camps near the end of the war.

In what sounds almost like a cliché, James Cleveland Owens was born on Sept. 12, 1913 to a poor sharecropping family, the grandson of slaves.

In trying to do what was best for the family, Owens’ parents (Henry and Emma) moved the family from Oakville, Alabama, to Cleveland, Ohio, when Owens was just nine years old.

Two things that would shape Owens’ life occurred from the move to Ohio.

The first being how he arrived at his moniker. As a young boy growing up in the South, everyone simply called James by his first two initials, “J.C.”

Upon his arrival to the Cleveland public school system, his name quickly changed.

Apparently, when one of his teachers asked him what he preferred to be called, Owens replied, “J.C.” His teacher mistakenly thought he had said, “Jesse” and James Cleveland Owens from that day forward became known as Jessie Owens.

The second thing that would forever shape Owens’ life is that he began to run.

Owens was a bit sickly as a child and was diagnosed with asthma. He was encouraged by doctors to run to build up his lung capacity. And run he did!

Owens first achieved national acclaim as a junior high school student.

Owens’ talents were first recognized by his physical education teacher, Charles Riley, at Fairmont Junior High in Cleveland.

Under Riley’s tutelage, Owens set two junior high school world records. The first was in the long jump, and the second in the high jump.

Owens achieved his first world record while in high school by running a blistering 9.4 seconds in the 100-yard dash.

At the 1933 National Interscholastic Championships, held in Chicago, Owens won three events in leading his high school to victory.

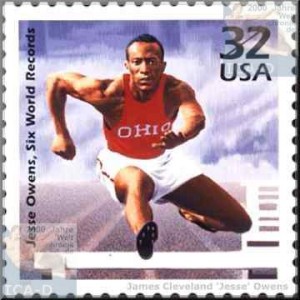

n 1998, the United States Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp depicting Jesse Owens competing in a hurdles event at Ohio State University.

Later that year, Owens turned down many scholarship offers and instead chose to enroll in Ohio State University and work his way through school as Ohio State, at the time, had no scholarship to offer him.

On May 25, 1935, Owens, in a single day, broke three world records and tied another at a Big Ten track meet in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

He achieved all this from 3:15 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. that day. Three world records broken in roughly 45 minutes!

Over half a century later, this achievement prompted renowned sportscaster Bob Costas to choose it as one of the best individual sports achievements in history.

One thing that gets lost in the grandeur of Owens’s accomplishments is the significance of his world record in the running broad jump (now known simply as the long jump). Owens’ mark of 26′, 8-1/4″ stood for 25 years, and he made only one attempt!

Not until Ralph Boston started shattering long jump records in 1960 would the world see this mark eclipsed.

Not even Bob Beamon’s freakish jump (29′, 2 1/2″) at the Mexico City Olympics stood longer than Owens’ mark.

Beamon had bested Boston’s mark by an incredible 2′ and 1-3/4″, a mark which stood for 23 years until Mike Powell sailed into the books with a leap of 29′, 4-3/8″.

Then came the 1936 Olympics.

It should be noted that Owens came quite close to not even medaling in one event and not participating in another.

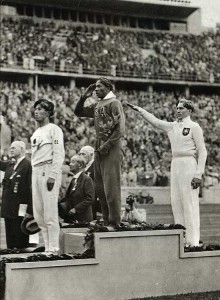

On Aug. 3, Owens beat fellow African-American, Ralph Metcalfe, in the 100-yard dash finals for his first Gold Medal.

Owens won four gold medals at the 1936 Olympics.

On Aug. 4, the running broad jump (now known as the long jump) almost derailed Owens’ quest for Olympic history.

During the preliminaries, Owens fouled twice and was shocked and dismayed when officials counted what he thought was a practice run as an official attempt.

Down to his last jump, one of Owens’s main rivals and German team member, Luz Long, advised Owens to move his takeoff mark back a few inches back to ensure a “safe” jump.

Owens took the advice and advanced to the next round.

Long and Owens both made the finals and on Long’s fifth attempt he matched Owens leading mark of 25′, 10″.

In his last jump, Owens broke the Olympic record with a leap of 26′, 5-1/2″.

The first to congratulate him was Long. This is what Owens had to say about that moment:

“It took a lot for courage for him to befriend me in front of Hitler. You can melt down all the medals and cups I have and they wouldn’t be a plating on the 24-karat friendship I felt for Luz Long at that moment. Hitler must have gone crazy watching us embrace. The sad part of the story is I never saw Long again. He was killed in World War II.”

On Aug. 5, Owens set another Olympic record in the 200-meter dash. He bested fellow American Mack Robinson, an older brother of Jackie Robinson.

Owens thought his Olympics had come to an end, as he had finished all three events he had planned on competing in.

However, Owens was asked to compete on the U.S. 4×100 relay team.

Rumor had it the U.S. Olympic Committee had, at the request of the German Olympic Committee, removed Marty Glickman and Sam Stoller from the 4×100 relay team.

Glickman and Stoller were the only two Jews on the entire U.S. track and field team.

It seemed Hitler and the Nazis had had enough of Owens’ antics and didn’t want to be further embarrassed by being bested by the American team with the contributions of the two Jewish-American athletes.

On Aug. 9, Owens garnered his fourth gold medal by running leadoff for the Americans. They set a world-record in a time of 39.8 seconds, a mark that would stand for 20 years.

One myth of the 1936 Games was that Hitler snubbed Owens by refusing to shake his hand.

At the beginning of the games, Hitler had made it a practice to shake the hand of all the winning German athletes.

He was advised to stop this practice because, as host of the Games, he was supposed to remain neutral.

This happened prior to Owens’s participation in the Games, and was not made known to the American media at the time.

When Owens won his first event and a Hitler handshake was not extended, the myth was born. Something even Owens tried to squelch at one point:

“When I passed the Chancellor he arose, waved his hand at me, and I waved back at him. I think the writers showed bad taste in criticizing the man of the hour in Germany.”

Owens later said:

“Although I wasn’t invited to shake hands with Hitler, I wasn’t invited to the White House to shake hands with the President, either.”

After his historic Olympics, Owens returned to the U.S. to make good on several endorsement offers.

However, in a bit of a Catch-22, he was stripped of his amateur status when American athletic officials caught wind of his endorsements.

The endorsements disappeared and Owens’s athletic career was over.

In the years after the Olympics, Owens found himself having to take anything and everything that came his way to make a living.

He would race against whoever challenged him…giving them huge leads and usually winning.

He even raced against dogs and racehorses to earn a buck.

The first American to win four gold medals in an Olympics became a gas station attendant to feed his family.

To add insult to injury, Owens had to file for bankruptcy and, in 1966, was convicted of tax evasion.

After nearly 30 years of what should have been post-Olympic glory, the tide started to turn for Owens.

Owens became a professional speaker and opened his own public relations firm.

Owens is pictured showing off his four Olympic Gold Medals. He was awarded the Medal of Freedom by President Ford and following his death received the Congressional Gold Medal.

He would lecture to major companies around the world, The International Olympic Committee, and even to our nation’s youth.

President Gerald Ford awarded Owens the Medal of Freedom for his achievements in overcoming race, hatred, and bigotry.

After a lifetime of smoking, Owens succumbed to lung cancer on March 31, 1980.

He was posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal by President George H. W. Bush in 1990.

In 1983, Jesse Owens was inducted into the U.S. Olympic Committee Hall of Fame.

In closing, I would like to leave you with a final thought from the incomparable Owens:

“The battles that count aren’t the ones for gold medals. The struggles within yourself—the invisible, inevitable battles inside all of us—that’s where it’s at.”

Blaine Spence is an occasional contributor to Sports Then and Now.

WAS THERE AN AMERICAN AWARDED THE FRANCE MEDAL OF HONOR IN THE LAST 6 WEEKS, FOR HEROISM DURING WWII?

I’ve learned a lot from your blog here,Keep on going,my friend,I will keep an eye on it,thanks for your post!welcome to 许昌374楼论坛.

Hello! Do you know if they make any plugins to help with SEO? I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good success. If you know of any please share. Appreciate it!

I used to be recommended this website by means of my cousin. I’m now not certain whether or not this put up is written by means of him as nobody else understand such targeted about my trouble. You are incredible! Thanks!

Awesome…please update me when the new version is up!

This piece of writing presents clear idea designed for the new viewers of blogging, that

genuinely how to do blogging and site-building.

Here is my webpage: snoop dogg g pen