Pancho Gonzalez: A Posture of Resistance

Like a hardened tree, Pancho Gonzalez exhibited the posture of resistance.

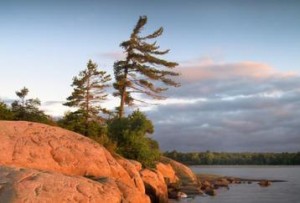

Not far from my place, there stands an old windswept pine, so hardened by the elements that even on a calm day it exhibits the posture of resistance. It seems unrelenting in its refusal to bow.

More than once, the old tree has symbolized for me the human traits of stubbornness, perseverance, endurance and toughness. Its sinewy skin and tightly-clenched roots tell of a life filled with challenge and pain. Yet it still stands there in defiant victory.

That sun-bleached, aged pine has not merely survived…it has actually thrived. The perplexity of that thought has often brought to mind a particular person. As I set about to research this story, it became clear that my subject was one such person.

Ricardo Alonso Gonzalez, the son of Mexican immigrants, faced the winds of adversity from the onset of his tennis career.

As a young minority teen-ager in 1940s Los Angeles, he was shunned by the upper levels of society. Gonzales often spent time watching tennis enthusiasts unwind at neighborhood parks and public courts.

He was intrigued by the combination of power and finesse that tennis required and would emulate the moves he so diligently observed through the fence. Thus was laid the self-taught foundation of Pancho Gonzales’ fabulous career.

Tennis became his obsession and predictably, his studies and social skills suffered. Truancy and trouble with the law soon followed. Then, a year of juvenile detention.

Though his talent was by now undeniable, his rowdy reputation and cultural roots ensured his exclusion from LA’s upper-crust tennis clubs.

Gonzales persisted, training on the public courts, and by the age of 20, he surprisingly won his first U.S. Championship title. He followed up with another U.S. title the next year and in 1949 he turned pro.

Pancho Gonzalez was intrigued by the combination of power and finesse that tennis provided.

Between 1952 and 1961, he won eight U.S. Professional Championships and was regarded as the best player in the world in that span.

In those days, Grand Slam tournaments were amateur-only, denying Gonzales entry due to his professional status.

One can only estimate the number of Grand Slam titles he might have won between 1949 and 1968, the year the Slams were finally “open” to professionals.

Gorgo, as he was known in tennis circles, consistently dominated the likes of Frank Sedgeman, Tony Trabert, Ken Rosewall, Lew Hoad and Roy Emerson during his glory years. He prospered by relying on one of the most feared serves ever in men’s tennis – and a potent net game. He was equally adept playing on grass or clay.

At well over six feet tall, his imposing presence was enhanced by a panther-like quickness. The most devastating weapon in Gonzales’ arsenal however, was his competitive fire.

Some who knew him might argue it was his off-court conflicts which fueled that fire into a burning will to win. Others in his inner circle took that perception a step further, considering it more of a “rage” to win…

Known to be temperamental and sullen, Gorgo was generally not well-liked and seemed to relish the life of a loner. His six marriages testify to his fierce independence and hot temper.

In a career extending long past his peak years, Pancho continued to compete at a high level well into his 40s, eventually hanging up his racquet at 44. His tenure at the highest level of competition included at least 91 singles titles and 10 pro tour championships.

For such a long and colorful career, one event remains as a vivid portrait of Gonzales the person, the athlete, the legend: an unforgettable match against his former student. It was Wimbledon 1969.

The record-setting contest was not a “Battle of the Titans” pitting No. 1 against No.2 in a climactic finals showdown. It was instead a first-round clash between a 41-year-old greying grandfather and a hungry young lion whom many at Centre Court considered the best first-day player.

The aging Gorgo, in a script appropriate for Hollywood, was to meet his rising understudy, 25-year-old amateur Charlie Pasarell.

What was predicted to be a competitive, yet routine battle turned into an epic 5 hour, 12 minute war: the longest match in Wimbledon history.

Set One

Interest and attendance was high for this particular match as the Wimbledon crowd had seen little of Gonzales over the years, due to the professional ban during his prime.

The student/teacher relationship provided an element of intrigue. Pasarell’s ascending status among the tennis elite helped fill the seats as well.

The tie-break had not yet been instituted in tennis, so combatants simply played on until one player achieved the two-point margin of victory.

The first set established the tone for the entire match.

Between Gonzales and Pasarell, there were 45 held serves. Neither player established a dominance. It was basically a point/counter point struggle.

This single set took on the characteristics of an entire match, with fatigue and muscle cramping eventually affecting play…especially for the elder pro.

Finally, as the sun was sinking low, the young Puerto Rican upstart placed an exquisite lob in Pancho’s backhand corner for a winner on his 12th set point.

Game (24-22) and set (1-0) to Pasarell.

Set Two

Physically weary and with daylight fading, Gorgo made repeated requests to suspend play. The umpire, Harold Duncombe, was firmly and curiously unrelenting.

When the fiery missile of Pancho’s will met the brick wall of Duncombe’s refusal, a classic Gonzales tantrum ensued.

As a statement of protest, Gonzales reportedly threw the set. After play was postponed, he stormed off the court, refusing the customary bow to the Royal Box.

A stunned crowd, which had been equally divided in their support, became unanimous in their boos.

Game (6-1) and set (2-0) to Pasarell.

Set Three

For Pancho, the bright morning sun was symbolic in its contrast to the dusky hues of the previous night. He seemed energized and gathered mentally, ready for the task at hand.

Pasarell appeared willing to continue his tactics of the first day: repeatedly hoisting lobs, hoping to tire the seasoned legs and neutralize the net game of his former teacher.

“Charlie, I know what you’re doing…and it ain’t working!” hissed Gonzales on a changeover. Was the teacher exploiting a known weakness in the student?

The set progressed as a tit-for-tat affair, both men holding serve. At 4-4, Gorgo’s once deadly serve began to shorten and Pasarell’s became stronger. Momentum started to swing in favor of the younger man.

Then oddly, as if taking to heart Poncho’s earlier verbal jab, Pasarell deserted the lob and reverted almost exclusively to his forehand. It failed him twice, in crucial chances to break serve at 8-8 and 10-10.

The 41-year-old Gonzalez treated spectators to one of the greatest opening round matches in Wimbledon history in 1969.

With Gonzales up 14-13, the young Puerto Rican prolonged the set (and saved set point) with three straight service aces. Then, serving again at 14-15, Pasarell betrayed himself with two disastrous double-faults.

Gorgo broke serve with a brilliant forehand pass – and another titanic set, which included 29 held serves, was over.

Game (16-14) and set (1-2) to Gonzales.

Set Four

The double-faults clearly unhinged Pasarell’s concentration. Smelling blood in the water, Gonzales began to envision victory, even as his body was beginning to wilt.

The boos of the previous night were all but forgotten as the crowd came alive, sensing the history being played out before them. Pancho, rather than Charlie, seemed to feed off the buzz.

By now, both men were beginning to struggle physically. At 3-3, Gonzales found success in moving his opponent back-and-forth across the baseline, peppering him with angled shots.

Two lost serves and another critical double-fault by Pasarell brought the match to even.

Game (6-3) and set (2-2) to Gonzales.

Set Five

Like two punch-drunk heavyweights, the combatants staggered to their opposite ends for the decisive set. In 1969 there were no timeouts for TV or rest stops at the changeover. It was a quick swipe with a towel and a swig of water…period.

The June sun was now high in the sky. Fatigue had stolen the sting from both players’ power strokes. They resorted to caressing the ball with english and finesse. Pasarell had returned to his lob. Gonzales leaned on his racquet between points, gasping for air.

Despite his age and more than five hours on the court, Gonzalez found a way to win.

As if dancing with death, Gonzales served at 4-5, down 0-40. Pasarell sent two lobs just wide and Gorgo hit a center-line ace to wipe out three match points and get to deuce. Six deuces later, Pancho saved his serve, 5-5.

Gaunt and grey, on the verge of the crippling stages of dehydration, the die-hard Mexican looked every bit the part of a haggered old tree still refusing to bow to the elements.

At 5-6, and again down 0-40, Gonzales found a reserved vigor and hit a smash, a cross-court volley and another ace to erase three more match points and draw even at 6-6. He saved another match point at 7-8. Riding a wave of successful first serves, Pancho became the aggressor, Charlie the defender.

After fighting off seven match points, Gorgo had the “dignified” Wimbledon crowd worked up to a lather as if it were World Cup Finals.

Finally, at 9-9, Pasarell faltered and lost serve at love.

Then, in the 112th game, Gonzales valiantly held serve as Pasarell’s lob at match point went long.

Game (11-9), set (3-2), and match to Gonzales.

If the tennis gods were cruel in depriving Wimbledon of Pancho’s presence during his prime, they at least were benevolent in granting her this spectacle…and on Centre Court at that!

Pancho Gonzales somehow recovered enough to win his next two rounds, then lost to Arthur Ashe in the quarterfinals. In an all-Aussie final, Rod Laver defeated John Newcombe in that memorable event, Wimbledon 1969.

To say that Gonzales influenced the game of tennis would be an understatement. This match in particular provided the impetus to finally institute the tie-break: a scoring concept which had been gradually gaining favor among the players.

Its intent was to shorten sets which had progressed to a 6-6 impasse. At that point, the tie-breaker would come into play, presumably to hasten the set’s outcome.

Earlier in Gonzales’ career, rule changes were introduced to handicap his dominant serve and immediate approach to the net. When Gonzales simply found other methods of domination, the rules were disbanded.

For over 25 years, Gonzales had an endorsement deal with Spalding. Then, after retiring from competitive tennis, he was Tournament Director for Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas for 16 years.

Yet when he died of cancer in 1995, he was virtually penniless and friendless…except for his last wife, Rita, and their two children. Rita’s brother, Andre Agassi, paid for his funeral.

~ ~ ~

There is no telling how many Grand Slam titles Gonzalez might have won had the major championships been open to professionals prior to 1968.

After having drafted this piece, I went back to visit ol’ Mr. Pine Tree. I don’t know why, but I was half expecting him to be leaning a little lower, colors a little more pale…

Nope. He was still standing tall, showing the ravages of time for sure, but proud and very much alive, not unlike my memories of one of tennis’ all-time greats.

We keep our heroes alive by celebrating our memories with others who knew them and by introducing them to others who did not.

I hope Pancho Gonzales came alive for you.

With this piece, we welcome Rojo Grande to the Sports Then and Now team.

Sources: tennisforum.com

guardian.co.uk

wikipedia.org

news.bbc.co.uk

nytimes.com

Poncho photos: 1. bmarcore.perso.neuf.fr

2. josealamillo.com

3. zing.vn

4. thaindian.com

Great story! I remember the score, but didn't know any of the details.

For some reason, I have been thinking about Pancho lately, and decided to look up more info on him. I played him in a mixed 45 Senior Tournament about 20 years ago. I, being the female of the mixed, happened to be better than his partner or he would have killed us! He was in his late 50's at the time. He was phenominal! I was in awe just playing against him. After we beat them, he nicknamed me "animal" and said he hadn't seen a woman's forehand like mine. He and I became partners for a couple of senior tournaments. I use to watch him workout with his three-year old son, Skyler, in Las Vegas. I am wondering if Skyler ever took up the game. My trophy was a license plate holder that said, "I Beat Pancho Gonzalez" Of course, I never put it on my car and I didn't really beat him….we beat his partner (he didn't see too many balls).

Anyway, what a wonderful article you have written about him. Thanks, Sharon Nichols, Dana Point, CA.

I’ve been following your web logs for 6 weeks now and i should tell i am starting to like your blog. How do I subscribe to your web log? how to build muscle quick

You ought to really moderate the remarks at this site

Mexican League stuff is great info

Awesome job

Wonderful post shared

Just read your article. Good one. I liked it. Keep going. you are a best writer your site is very useful and informative thanks for sharing!

This place looks so calm and I am fond of this kind of places as my passion is visiting all these places. This picture has showed me the way of my new dream that I should follow because I want to live my dreams.

nice article, thanks for sharing…

What a information of un-ambiguity and preserveness

of precious familiarity concerning unpredicted feelings.

nice post keep it up

Nice and interesting post

Have a cool post…

this is the best post

Useful ideas sharing dear keep it up.

Wonderful post thanks.

write my essay for me reviews