Roy Emerson: Master of the Grand Slam

Roy Emerson was the first men's tennis player to win 12 Grand Slam titles.

The best tennis had to offer chased this man for over 30 years. In 1967, Aussie great Roy Emerson won his 12th Grand Slam singles title at the French Open Championship against countryman Tony Roche.

After years of Bjorn Borg, John McEnroe, Ivan Lendl, and a legion more, no one equalled this mark until Pete Sampras tied Emerson’s single Slam total at the Wimbledon Championships in 1999.

The American surpassed Emerson, winning his 13th at Wimbledon one year later in July of 2000. As far as Sampras was concerned, when he took the U.S. Open title in 2002, winning his 14th and final Grand Slam victory, the record was his hopefully for another 30-plus years.

Sampras, however, was passed by Roger Federer in 2009—a mere seven years later, again setting his new record on the fabled Wimbledon lawns. Federer currently holds 15 Slam singles titles.

Emerson, born in 1936, was part of the Australian golden era of men’s tennis in the the late ’50s, ’60s, and early ’70s. During this reign of supremacy, no one contributed more to the aura of Aussie domination than Roy Stanley Emerson—a farm boy from Blackbutt in Queensland.

Considered “tall,” Emerson, at 6’0″, towered over his contemporaries, which would not be the case today. According to his biographers, who tout his milking regimen as the reason for his astounding wrist strength, being a farm boy also served its purposes.

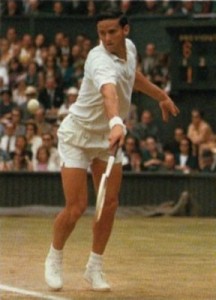

The truth is that Emerson—“Emmo” to his friends—was sublimely fit, as he trained hard to go the distance. He loved the challenge and rigors of five-set majors. His results in Grand Slam finals show his fitness served him well.

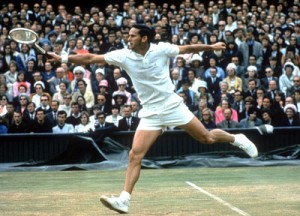

On court, Emerson preferred to serve and volley, but he could adapt his game to any surface—as he proved by winning the French Open twice during his career. Opponents feared his quickness, his ability to cover the court and his volleying skills.

Emerson typified Aussie spirit with his never-say-die attitude, his love of partying and his simple belief that once you took the court, you were fit enough to play—no excuses allowed.

Emerson “went the distance” 28 times in Grand Slam finals, winning 12 singles titles and 16 doubles. The Aussie holds the record for the total number of Grand Slam championships for men.

Emerson won the Australian Open six times and claimed each of the other three majors twice.

In singles, he won the Australian Open six times—in 1961, 1963, 1964, 1965, 1966, and 1967. Emerson’s six Australian titles along with his five consecutive wins there are records that still stand.

During his eight-year Slam winning spree Emerson also captured two Wimbledon titles in 1964 and 1965. He was denied his third consecutive win at the All England Club during a fourth-round match with countryman Owen Davidson.

Emerson skidded into the umpire’s chair while chasing down a ball. He injured his shoulder, and, even though hurt [no excuses], finished the match but lost.

The Aussie won the U.S. Open Championship in 1961 and again in 1964. French Open victories came in 1963 and 1967.

As good as Emerson was in singles, he was even better in doubles. He won 16 titles with five different partners and was so great that his contemporaries claimed the Aussie right-hander could win with anyone and make them look good in the process.

He won his last Slam doubles title in 1971 playing with Rod Laver on the grass at Wimbledon. He most often partnered with left-handed Aussie Neale Fraser, winning four of his Grand Slam doubles titles and three Davis Cup doubles matches with the lefty.

Contemporary Jack Kramer, who passed away in September of 2009, wrote of the Aussie great that “Emerson was the best doubles player of all the moderns, very possibly the best forehand court player of all time. He was so quick he could cover everything. He had the perfect doubles shot, a backhand that dipped over the net and came in at the server’s feet as he moved to the net.”

Emerson remains the only male player to have won singles and doubles at all four majors.

The Aussie’s only missing “trophy,” so to speak, is the absence of the true “Grand Slam” won during the calendar year. The closest Emerson came was in 1964, when he won three Slams but was ousted during the quarterfinals of the French.

His best year on tour, however, was 1964, when he won 17 tournaments and 109 of 115 matches and ended the year with the No. 1 ranking. One of those victories was his first ever Wimbledon Championship, which he won by defeating fellow Aussie Fred Stolle.

During the year he also led the charge in Davis Cup play. Emerson remained undefeated in eight singles matches as the Aussies regained the Cup finally by defeating the Americans on clay in Cleveland.

As a true leader Emerson was good at invoking and challenging his team to victory. He played on eight winning Davis Cup squads between 1959 and 1967. They credited him with firing up the troops and digging in when it looked bleak to win those five-set marathons.

The Aussies not only played together well, they played against each other with equal vim and vigor. Emerson and Laver often found themselves in the finals, battling it out to see who would wear the crown on that day.

All of Emerson’s single’s titles, except for the French, were won on grass. They were also won prior to the “Open Era” in men’s tennis. This demarcation is like a line in the sand when it comes to judging accumulated records and must be taken in to account as we attempt to compare players across time.

The Open Era of tennis began in 1968. This tore down the barricades, allowing professional players to participate in world-class tournaments. Prior to the Open Era, only amateurs could enter most prestigious events, including the Grand Slams. This left many of the top players of the day out of the competition. Simply put, players stayed as amateurs so they could compete in the Slam tournaments.

Shown are four of the greatest tennis champions of all-time: Pete Sampras, Emerson, Billie Jean King and Roger Federer.

Those that needed the money turned pro and some of the best players of the day were not allowed to compete at the Grand Slam tournaments. Today, that fact leads to speculation about how many titles might have been won during this era if pros like Pancho Gonzalez, for example, had been allowed to compete.

After years of negotiating for change, the governing bodies of tennis saw the advantages of open competition. When they allowed professionals to participate, the quality of competition increased dramatically while the popularity of tennis surged and prize money for the players skyrocketed. Tennis never looked back.

Players like Emerson who stayed as amateurs did so for the love of the game and the spirit of competition. Trying to asterisk their accomplishments is an injustice. They played by the rules in place at the time. They earned their places in the history books at a time when they received little or no compensation for their efforts.

Roy Emerson went on to be inducted into the Tennis Hall of Fame in 1982. He was not only one of the greatest Aussies ever to play the game—he was one of the greatest men ever to play tennis on courts across the continents of the world…

don’t fight you are unprepared for this. you need a trainer not just equipment and you need more than just a month

This website has got a lot of really helpful information on it! Thanks for sharing it with me!

Re: The person who made the comment that this was a great website truly needs to get their head inspected.

Soon, blacks were stepping into more controversial roles, more so than Latinos and even some white actors.

That is the reason why she has the show America’s Next Top Model, to groom other girls to become

healthy supermodels. It is also a way for shoppers to stock

up on hardto find D-Cup bikinis, DD-Cup Swimwear, DDD-Cupswimsuits and

E-Cup bikinis as well as beachaccessories including cover-ups,

sandals and sexy dresses for resortwear.