Great Men of Tennis: Dwight Davis; Gerald Ford of the Tennis World

A new series for a new year. In a companion series to ‘Queens of the Court,’ ‘Great Men of Tennis’ takes a look at the men who have left an indelible mark on tennis. The series begins among the foundations of our modern game, with the man who invented aspects of the serve, and set the stage for Davis Cup competition: Dwight Davis.

In honor of Dwight Davis, this article is posted on the 110th anniversary of the first Davis Cup – held Feb 9, 1900.

The Davis Cup has been an important part of tennis history for 110 years.

Let’s see, Secretary of War? Or famous tennis star? Hmmm … Which career path to choose? How about both?!

Not many tennis stars go to college. John McEnroe, who is famously known for attending Stanford, really only attended the university for a single semester. John Isner, a current tennis star, is the only one in the top 50 to obtain a degree (at the University of Georgia) before starting his ATP career this year.

Like John Isner, Dwight Davis was a collegiate tennis singles champion. He played for Harvard University in 1899. The closest he came to a singles title was runner up in the US Championships in 1898. A lefty, Davis made a name for himself in doubles. While at Harvard he also went out for baseball and played on the sophomore football team.

Quite a few US politicians were collegiate, or even professional athletes, before embarking on a life of public service, among them: President Gerald R. Ford, and Senator Jack Kemp. Dwight Davis can be counted among these public figures. Davis would serve the U.S. as secretary of war from 1925-1929 under President Calvin Coolidge.

In spite of his dearth of singles titles, Davis serves as a keystone for our ‘Great Man of Tennis,’ because Davis, like Frenchman Rene LaCoste 30 years later, was not only a winner but also a technical innovator, and became a key mover and creator in the sport.

Like many tennis stars of his day, Davis was from an upper class family, one of the founding families in St. Louis Missouri. At the turn of the twentieth century, tennis was played in society clubs, and also in the street. To distinguish its form of tennis from that in the street, club tennis was known as ‘Lawn Tennis.’ An iconoclastic visual of the times comes from the musical ‘Ragtime,’ which depicts turn-of the century upper-class types in the opening vignette as ‘fellows with tennis balls’ in 1902, in New Rochelle New York; straw hats, slacks, afternoon tea, and a spot of tennis.

The legacy of Dwight Davis continues to shape tennis 110 years after it was first awarded.

Harvard University was the Nick Bollettierri’s of its day, with 30 courts, and the top players of the time, practicing and innovating the sport. Dwight Davis’ peers at the time were (with delightful, turn-of the century names): Holcombe Ward, Malcolm Whitman, Beals Wright, Leo Ware, and William Clothier (US singles champion in 1906). The period 1898-1906 has been called the first golden age of American lawn tennis (the second golden age being 1915-1930 with Bill Tilden and Bill Johnson.)

Among innovations in the sport coming from these players: a special top-spin slice serve that after bouncing would break rightward in the direction of a right-hander’s backhand, created by Holcombe Ward and Dwight Davis to defeat Malcolm Whitman. All three players would later serve as the original members of the US Davis Cup squad. The innovation was at first called the American Twist Serve, but now is simply called a ‘kick’ serve and used effectively on second serves.

Perhaps the most exquisite contribution Dwight Davis made to the sport was his willingness and ability to commit the resources to create a competition, one of the most formidable international competitions in any sport outside of the Olympic movement, known originally as the International Lawn Tennis Challenge, which was later renamed the Davis Cup in his honor.

Tennis has ancient origins – stretching some say back to the Egyptians – but the modern game began to take shape in France and England, as well as the US, in the timeframe after the US civil war. It was in this timeframe (1877) that the first championships were held at Wimbledon.

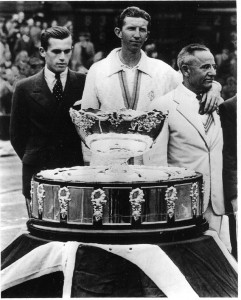

Don Budge and the team from the United State won the 1937 Davis Cup.

The International Lawn Tennis Challenge (Davis Cup), issued in 1899 by four members of the Harvard tennis team, was conceived for the purpose of a single tennis squad (Harvard) to challenge the British to a tennis competition. Dwight Davis designed the tournament format and commissioned from his own funds an exquisite solid sterling silver trophy (Dwight’s Pot) from Shreve, Crump & Low, a popular silver-casting outfit at the time in Boston.

Ironically for someone who would go on to serve as Secretary of War, Davis was stalwart in his vision for the competition, and for the compelling international nature of tennis. As innovative as they were, and as deep in talent at Harvard, Davis and his peers would read articles from London about the level of play in the United States. Among the comments: America had good players, but they didn’t pay enough attention to the ‘fine points’ of the game and, besides, their backhands were weak. Davis and his contemporaries, eager to prove the manner in which their innovations had caused the sport to progress, issued a challenge to their British counterparts, and devised the team format to illustrate the depth and breadth of any given countries skills at the sport. Like the modern Olympics, which were re-conceived in the same timeframe, the Davis Cup was seen as a unifying influence, one that fostered international cooperation and understanding by focusing on the technical achievements of sportsmen.

It was perhaps his prowess at doubles, where team-work was more important, that led Davis to experiment with the team format. In this, the Davis Cup, as a sporting event, differs from the tennis majors, which can also be seen as international events in their modern incarnation, but in which each individual’s technical skills are the lynchpin of their success.

The 2004 Davis Cup team for Spain was dubbed the Dream Team.

The first Davis Cup competition was held in 1900. By 1904 the French were included, by 1906 the Australians were included, and the list of participants, and the ends of the earth to which the players were willing to travel for competition, quickly multiplied. The desire on the part of some countries to capture the Davis Cup, and the lengths to which they went to win it, are the stuff of legend and history. We will visit some of that history with the discussion of Rene LaCoste and the rest of the Four Mousequetaries later in this series, for by now Davis Cup competition is firmly entrenched in tennis lore.

Davis remained dedicated to the principles of Davis Cup competition for his entire life. Davis is recorded as saying that his vision for the Cup must not be forgotten, “It is meant to travel. Its appearance in any country brings a flock of exterior implications very beneficial to sporting unity in the tennis world.”

Check back next week for more Great Men in Tennis with the next in the series: Don Budge. For more in the series, see the following:

- Dwight Davis

- Bill Tilden,

- Rene Lacoste

- Gottfried von Cramm

- Don Budge

- Fred Perry

- Jack Kramer

- other Musketeers

- Pancho Gonzalez

- Roy Emerson

- Ken Rosewall

- Rod Laver

- Ilie Nastase

- Lew Hoad

And check out the companion series: ‘Queens of the Court’

Thank you for a great article! We love hearing stories of our legendary trophies and awards! (And we're still being commissioned to make awards today!)

Shreve, Crump & Low

440 Boylston Street

Boston, MA

Wow! thanks for posting, Deborah! I'm so impressed that the company is still around. The Davis Cup trophy is one of the most beautiful trophies I have ever seen. (I've never seen it in person, of course).

Wonderful, wonderful article!! Great foundation for the upcoming Davis Cup challenges! It is amazing how long the Davis Cup has persisted even without participation by some of the top-ranked players. It is too bad the ITF and the ATP cannot work together to give the the Davis Cup the spotlight in the all-to-crowded calendar!! Great stuff!

Wow, you managed to find a tennis player I know nothing about.

Good work on the article, too.

Sometimes the site loads slowly, but great material.

Magnificent website. A lot of useful info here. I am sending it to several buddies ans additionally sharing in delicious. And obviously, thank you in your effort!

I just like the helpful info you supply to your articles.

I’ll bookmark your blog and check again right here regularly.

I’m somewhat sure I’ll be informed lots of new stuff proper right

here! Best of luck for the next!