Is The Super Bowl Bigger Than Rugby’s Six Nations Championship?

In Some places, the Rugby Six Nations Championship is bigger than the Super Bowl.

You’d be forgiven—if you are American—for thinking that the entire sporting world fell into awed silence as the brouhaha that is Super Bowl swept along everyone with even the faintest of pulses.

And of course this year’s spectacle had the extra wow factor of an emotional New Orleans back-story: underdog, triumph over adversity, not a dry eye in the house.

For many on the other side of “the pond,” though, that New Orleans back-story was the front story, too, because American football remains an impenetrable anachronism for most of us…well for this particular correspondent, anyway!

So last weekend, our focus was rather more Euro-centred. While the padded up and helmeted Superbowl heroes began their campaign to the predetermined rhythm of the broadcasters’ advertising breaks, its stripped down, bare-knuckled equivalent—the Six Nations Championship—was just getting under way.

This is a competition where deep-rooted loyalties have been determined by the history books, with the English the common foe. It may be hundreds of years since a king Edward or a king Henry strode into Scotland or Wales, Ireland or France, but an unspoken resentment still simmers in the veins.

That complex tapestry of history, married with the visceral sport that is rugby union, makes the Six Nations championship one of the most intense and compelling competitions in sport.

[poll id=”63″]

History Writ Large, Even On The Shirts

The opening day of the Championships was a special one. It was the centenary of the first match played at “HQ,” Twickenham stadium itself. On that day in February 1910, the same two teams took to the field, and produced the same result: England defeating Wales.

For some of the players, this Championship has personal “centenary” significance. Colin Paterson will celebrate becoming the first Scot to win 100 caps when his team meets Wales this week. On the opposing side, Martyn Williams will notch up 100 international caps should he make it through all five matches of the Championship.

But back to that England centenary. The occasion was marked by a team kitted out in a special strip that cast a sentimental eye back to the beginning of the last century. In design and colour, it recalled the traditional heavy-duty collared shirt that, even in 1910, had looked back to the Rugby School of the 1880s for its inspiration.

It took a moment, though, to spot what was odd about the strip: in its essentials, it was not wholly different from today’s strip. No, what was missing was the branding, because the England team’s sponsors had, for this one day, sacrificed their full-blown logo.

It’s All In The Timing

In a world where sport and broadcasting are dominated by the demands of sponsors, it comes as a breath of fresh air for television advertising to be structured around the match rather than the other way round.

While the Superbowl can stop and start its way towards four hours, rugby’s internationals go at full tilt for under two—and that’s including the formalities of introductions, anthems, and half time conflab.

It’s exhausting stuff, with little respite: a non-stop 40 minutes, a 10-minute break, and the concluding 40-minute-plus stretch. Fans take a comfort break at their peril, because the scoreboard will carry on without them: no-one leaves their seats.

Music to Swell the Heart

The singing of the crowd goes with rugby internationals like a dram of single malt in a strong coffee. It is the kind of singing—patriotic, soaring, lyrical and passionate—that catches the throat as the hot caffeine floods the bloodstream.

The English long for a song that can match Bread of Heaven at Cardiff’s Millennium Stadium, or The Flower of Scotland at Murrayfield.

Compare the maudlin melody of the British National Anthem with the rousing spirit of Le Marseillaise and it’s no surprise that the English fans have adopted something else. How it came to be Swing Low, Sweet Chariot is a mystery, but when Twickenham swells to its chorus, every heart swells too.

Can it match the Scots singing, to the accompaniment of the pipes, of their pride in sending Edward’s army “homeward tae think again?” Never.

Can it match the best choir in the world singing of loyalty to their homeland and the forefathers who gave their “life’s blood for freedom?” Of course not.

These are, after all, recalling the defence of their countries against the marauding English. No wonder there is such an intensity to these occasions.

Brute Force Tempered by Calm Poise

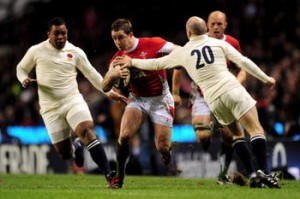

This is a sport of muscle and sinew, power and force. From scrum to lineout to tackle, its physicality and strength are writ large. The attack for a try may come from the ducking and weaving of the sprinting backs or from the charging shoulders of the front row.

But then there are moments when the hurly-burly ceases for a few oxygen-gathering minutes. These are the moments when one man is called upon to slow his heart, shut out the roaring crowd, and step up for a kick at goal.

He can be the match-saver or the match-loser, the team’s poster boy: England’s gilded Jonny Wilkinson or Wales’s glowering Steve Jones.

The ball is balanced, at just the right tilt, and steps are taken in careful measure, backwards and to the side. The target may be 50 metres distant, the angle may be acute, the target narrowed to a half-closed window.

Years of practice are concentrated into these short seconds of calm. The ball soars, the crowd roars, and all hell breaks loose once more.

The Royal Seal of Approval

You know a sporting occasion has a little something special when more than one royal turns up. And it adds an extra frisson when each of them is supporting a different team.

While the Super Bowl attracts American celebrities, the Six Nations Championship attracts royalty.

Cheering on England is Prince Harry, while in the adjacent seat is Prince William, on his feet, arms aloft, as Wales score a try. Their dad, of course, is the Prince of Wales—a bit of history that needs tucking under the carpet—as William will become in due turn.

Away, north of the border, is Anne, the Princess Royal. As is her wont, she dons tartan to support the team of which she is patron, Scotland. Her grandmother was Scottish, and is a more convincing reason for her allegiance than that her father happens to carry the designation “Duke of Edinburgh!”

A Family Affair

Rugby is characterised by, and proud of, its friendly camaraderie. This tournament also manages to mix in inexplicable family allegiances that are worn on the sleeve and hardwired into the DNA.

Imagine the scene. Best friends, one English, the other Welsh, live in the same town, have grown kids, and are gathered to watch their respective teams.

They text their absent children. Daughter Evans is watching the match in a bar in Hong Kong at 2 a.m. She is born English, has an English mother, but stands shoulder to shoulder with father Evans in her support of Wales. Son Evans, meanwhile, aligns with his mother and cheers on England.

The Englishman’s daughter, away for a girls’ weekend, is also watching, and instructing her friends in the finer points of offside and forward passing. She phones within seconds of the final whistle to share the moment of triumph, just as the Evans’ share the Welsh gloom of defeat. Then within minutes, it’s back to the ale, to impartial analysis, and to fresh conversations.

And there you have this sporting competition in a nutshell. The heat of battle gives way, in the blink of an eye, to a shake of the hand and a generous word, both on the pitch and off. It becomes one of those special occasions when sport moves beyond mere competition and rivalry to a unique shared experience.

In the end, then, not so different from the Super Bowl.

Whatever…