Great Men of Tennis:The Mellifluous Don Budge

There are names so ingrained into the tennis consciousness that one feels they’re still to be found gracing the Royal Box on Wimbledon’s Centre Court. The commentary team helpfully points out the faces to match the names. Rod Laver, Margaret Court, Ilie Nastase, Billie Jean King: They have become like family, like old friends.

Such is the case with Don Budge. A Grand Slam will not pass, nor a reference to “the greats of tennis” be made without his name being mentioned. And just lately, promoted by Roger Federer’s record-breaking feats, his name has appeared with ever greater frequency, bracketed alongside potential contenders for the “greatest ever” crown.

There is good reason for Budge to be one of those constants in the game. He was born way back in the Great War, achieved the first ever Grand Slam just as World War 2 was fermenting (and Rod Laver just a month old), and spanned the amateur and the professional age.

He played against the icons of tennis—Fred Perry, Bill Tilden, Frank Sedgman—and against modern greats such as Pancho Gonzalez.

As recently as 1973, aged 58, he teamed up with Sedgman to win the Veteran’s Doubles title at Wimbledon, so would have shared the locker room with men’s seeds such as Jimmy Connors and Bjorn Borg.

He lived—just—into the 21st century. Yet to modern fans, he is little more than a name. It’s time to put that right.

Budge came from good stock, from a bold father who upped sticks from Scotland at the turn of the 20th century for a healthier life in the warm climate of California.

Donald was born in 1915 and inherited his father’s sporty genes. Budge senior had played reserve for Rangers football team before he left for the New World.

Don was also bright—he went to the University of California at 18—and he was over 6’1” tall. He was, in fact, the perfect package for tennis.

As for his character, well Time magazine, which first featured Budge on its cover in September 1935, summed him up as:

“A phlegmatic, gentle youth, so homely that even his mother smiled when a friend said that, if not the best tennis player in the world, her son was certainly the ugliest, young Budge is likeable but undistinguished off a tennis court.”

His road to tennis was a familiar one. Budge tried, and was good at, many other sports, and excelled at baseball. It was his elder brother, Lloyd, who was the tennis player, and who persuaded Don to apply his fearsome bat-swinging prowess to a tennis racket.

He learned his trade quickly on the public hard courts of the West Coast and at just under 15, he won the California U15s Championships. That was his incentive to give up baseball.

By 18, he had won the National Junior Championships by beating the top contender Gene Mako, from a two set deficit.

At 19, he was picked for the Davis Cup auxiliary team and with that beckoning success, walked away from university to devote himself to tennis.

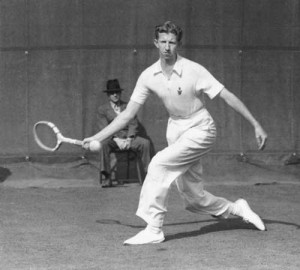

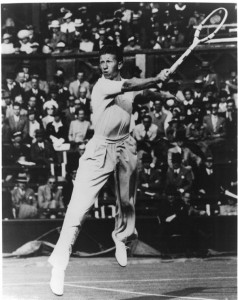

Budge was tall, almost 6'2", a powerful server, and athletic and fast about the court.

That Perfect Package

Budge had the classic all-round game founded on a powerful serve, strong and accurate ground strokes, and an effective volley. His graceful backhand, in particular, was regarded by most contemporaries as the best in tennis.

Frank V. Phelps wrote in The Biographical Dictionary of American Sports that “Budge exhibited power, consistency, and no weaknesses at his peak. He devastated opponents by serving and smashing with a slight slice, stroke-volleying deep and hard, and driving hard with minor over spin.”

In the rare fragments of film that can be found, he has a tall, slim, fluid elegance. Most striking are his long legs and ease of movement: a certain Fred Astaire look but much taller and topped by a shock of red hair.

The sporting genes shone through in his timing and rhythm, and the package was completed by a quiet yet confident application to improving his game. This mental attitude proved to be key in making his breakthrough to the very top of the game.

In 1935, Budge had beaten the heavy favorite, Bunny Adams, at Wimbledon before losing in the semifinals to the renowned Baron Gottfried von Cramm.

The following year, Budge lost at Wimbledon again, to Fred Perry, the No. 1 amateur at the time, and to von Cramm, 10-8 in the fifth set, in the U.S. Nationals.

So Budge took five months off over the winter to change his game. Alan Transgrove, in The Story of the Davis Cup, explained how:

“Don Budge’s greatness was as much the result of his eagerness to learn and adjust his technique as to his natural talent…While umpiring a match between two world-class players, he observed that one of the players hit the ball quite hard while his opponent hit very early while the ball was just inches off the ground. The unbeatable combination, Budge mused, would be a player that could hit the ball both hard and early.”

So he worked with his coach to put his theory into practice.

1937: A Year Of Change

In 1937, things finally fell into place. At 22, Budge was just entering his physical prime with a stronger, rebuilt game. He also saw his major rival, Perry, turn professional. By the time Budge reached Wimbledon, he had become the man to beat, and nobody could.

He became the first man to win the men;s singles, men’s doubles, and mixed doubles titles in the same year (and repeated the feat the very next year). Along the way, he beat his friend and rival von Cramm in straight sets.

A couple of weeks later, the same rivals were back at Wimbledon for the Davis Cup in what would become he highlight of the year. They played in front of Queen Mary, and had Adolph Hitler listening to the radio broadcast.

Budge had already won his singles and doubles rubbers, so by the time he walked onto Centre Court, the tie was equal at 2-2. The decider looked as though it would go to the German but, down in sets 2-0 and in games 4-1, Budge fought back to take the final set 8-6. It sealed the match and the tie for the United States.

Budge described it thus. “It was the greatest match in which I ever played. It was competitive, long and close. It was fought hard but cleanly by two close friends. It was cast with the ultimate in rivals, the No. 1 ranked amateur player in the world against the No. 2. I never played better and never played anyone as good as Cramm.”

Allison Danzig wrote in the book Budge on Tennis: “The brilliance of the tennis was almost unbelievable. In game after game they sustained their amazing virtuosity without the slightest deviation or faltering on either side.”

Budge and von Cramm, who played one of the finest Davis Cup matches in 1937, became great friends.

The Challenge round against England the next week, again at Wimbledon, once more saw Budge win all three of his matches and thus the Davis Cup for the U.S. for the first time since 1926.

Budge rounded off the year with another defeat of von Cramm in the finals of the U.S. Championships.

1938: The Landmark Year

Budge’s rivalry with von Cramm continued into the beginning of what would become a year for the record books. Budge twice lost to his friend in warm-up events for the Australian Nationals, but went on to win the Australian title for the loss of just one set in the entire tournament.

The rivalry between Budge and von Cramm, though, would not continue. In a sad turn of events, the German was imprisoned for his anti-Nazi stance and suggestions of homosexuality.

An outraged Budge collected signatures and wrote to Hitler. Von Cramm was released after six months, and attempted a return to tennis, but the rising political tension in 1939 denied him the chance to play Wimbledon or the U.S. Championships. He did return to amateur tennis after the war, by which time his old friend was a star of the professional tour, but they never competed together again.

The removal of von Cramm from the scene meant Budge would dominate amateur tennis for the rest of 1938. He beat Roderick Menzel in the French Open, Bunny Austin at Wimbledon, where he never lost a set, and Mako in the U.S. Open—again for the loss of just one set in the tournament. He became, therefore, the first person to win the tennis Grand Slam.

Just as impressive, and less well known, is that he became the only man to win six back-to-back Majors, with a 92 match winning streak.

Still Dominant As A Pro

At the time of Budge’s record-breaking run, of course, two of the best players in the world, Ellsworth Vines and Fred Perry, were on the professional tour.

Following his 1938 successes, Budge also turned professional, and so was able to assert his dominance over the pros as well.

He made his debut at Madison Square Garden in 1939 and, in front of a crowd of almost 17,000, defeated Vines in straight sets. He went on to score a 21-18 head-to-head against Vines and an 18-11 superiority over Perry. Against the 47-year-old Tilden, it was 51-7.

Budge topped an outstanding 1939 with titles at the French Pro Championships, beating Vines again, and at the Wembley Pro Championships, beating the title-holder Hans Nüsslein.

The tennis of Budge and his contemporaries was enthusing audiences across Europe, and the professional tour played to capacity crowds. This led to calls to combine the amateur and professional tours. Writers covering the pro events in Europe questioned the exclusion of the professional players from the Slams. The Daily Telegraph, for example, contrasted the empty seats at the 1939 Wimbledon final with the size of the crowds watching the power tennis on the pro tours.

Some believe it was only the coming of war that prevented the move to the Open era. It would, though, be another three decades before the moment was finally seized.

During 1940, Budge continued to dominate men’s tennis, winning four of the seven principal tournaments including the U.S. Pro Championship against Perry. But world events drove a scaled-down tour back to the U.S.

The demand for the big stars of the day—Budge, Tilden, Perry and Bobby Riggs on the men’s side, and the hugely popular Alice Marble on the women’s—continued to draw big crowds and raise money for war charities.

And despite a break for facial surgery, Budge was still the dominant force, with a 52-18 win-loss margin and victory in the U.S. Pro Championships.

Indeed, Tilden wrote that Budge’s standard of play “lifted all of us with him.”

The War Watershed

Don Budge was renowned for his grace and fluidity, and in particular for his famous backhand.

Since the middle of 1939, the Tour events in Europe were being cancelled as the political climate deteriorated towards war, and the pro series in the States drew to a halt in 1942.

Budge joined the U.S. Army Air Force for the remainder of the war. On exercises in 1943, he tore a shoulder muscle and surgery left him with scar tissue. Despite extensive osteopathy, it seemed to permanently affect his tennis.

As the war came to an end in 1945, he played some exhibitions for the troops. One such series was between the U.S Army and U.S. Navy: in effect, Budge versus Riggs. The series concluded, the first time, in Riggs’s favor, and the change in fortunes continued into the peacetime tour.

In 1946, the Budge vs Riggs head-to-head was 22-24, and one of Budge’s losses was in the final of the U.S. Pro Championships. It was a similar story in both the 1947 and 1949 finals.

In 1953, aged 38, Budge did reach the U.S. finals again, this time losing out to the new top man in tennis, the 25-year-old Pancho Gonzalez. Soon after, however, Budge drew a line under his Pro career.

There was one more triumphant moment afforded, appropriately enough, by the coming of the Open era of tennis. Budge, at the age of 58, returned to the scene of his greatest victories to win Wimbledon’s Veterans Doubles Championship with Frank Sedgman.

In December 1999, Budge had a car accident, and died a month later, aged 84. He left his second wife, two sons, and an indelible mark on tennis.

The Reputation

On paper, the Budge Grand Slam tally is not earth shattering: six singles, four doubles, and four mixed doubles. He also won only four professional championships. But context is everything.

Budge won his first three professional majors, the French, the U.S and Wembley, back to back, in 1939-40. But from then until the end of the 1940s, these events were suspended in Paris and London (and in the U.S. in 1944). So at the peak of his career, the door to more titles closed.

The best measure, then, is the judgement of those who played him and those who saw him. There, Budge’s reputation makes the earth shake with more conviction.

Tilden on Budge: “The finest player 365 days a year that ever lived.”

Kramer on Budge: “He was the best of all. He owned the most perfect set of mechanics and he was the most consistent.”

E. Digby Baltzell in Sporting Gentlemen: “[Budge and Laver] have usually been rated at the top of any all-time World Champions list, Budge having a slight edge.”

Tony Trabert (a winner of Wimbledon, the French, and the United States Nationals) on Budge: “He stands tall in the record books…His backhand was what we called a concluder, the sort of shot people will still be talking about a hundred years later.”

Unfortunately, those record books will never reflect Budge’s true talent and superiority.

The Man

Hardly a piece is written about Budge that doesn’t mention his popularity, his affability, and his gentlemanly manner. He seemed to be a man of intelligence, of courage, and of integrity, who gained friends easily and, far more difficult, managed to keep them.

Take Mako, who he played in the finals of the U.S. Championships in 1938. He played alongside Mako in that victorious Davis Cup squad of 1937. They went on to become a formidable doubles team, competing in seven Grand Slam finals, winning four, and they remained life-long friends.

Take von Cramm. Each had nothing but praise for the other man’s tennis and character. Despite vividly different backgrounds, they were alike in the essentials: courteous, sporting, generous in their praise.

On court, Time magazine in 1937 described them as “technically, almost twins. Both hit with apparently effortless length and accuracy, forehand and backhand; both have a deadly overhead, a stinging service. Both are stylists whose repertory takes in all the shots that tennis knows.”

Perhaps that is why they admired each other’s play so much. After their emotional Davis Cup match, von Cramm said: “Don, this was absolutely the finest match I have ever played in my life. I’m very happy that I could have played it against you, whom I like so much.”

Budge won many friends and fans by postponing his departure from amateur tennis so that he could help defend the Davis Cup title in 1938. In the event, he went on to make history with that decision, as well as to win another Davis Cup.

He also had many friends in the world of jazz—a passion he had all his life. In 1939, Tommy Dorsey promised Budge he could play drums with his band if he defeated Vines in his first match as a professional at Madison Square Garden.

Budge won, and that night Dorsey sat him at the drums in the New Yorker Hotel ballroom, saying: “My band is your band.”

Read an excellent piece, written in 1989, about Budge’s love of jazz.

Budge played in an era when life as an amateur without an independent income was hard and where the professional tour was gruelling. Add into the mix the political uncertainties of the late 30s, followed by the impact of war, and the achievements of players such as Budge are all the more outstanding.

They were, nevertheless, amongst the lucky ones who were able to take up their lives again in the late 40s.

Budge identified the great Helen Wills Moody as an important influence in his youth, and he would go to watch her play at every opportunity. He would also, eventually, have the chance to play doubles with his heroine during the mid-30s.

But he said of her: “I thought that if ever I became a champion, I’d want to behave just like her.”

He achieved both.

Here is a fragment of Budge playing at Roland Garros: 1.40 to 2.10.

Elegance personified.

Very thorough and comprehensive. It is great to read about these men who before were only familiar names but become flesh and blood through your descriptions…it seems every era has it issues and the WW2 was certainly a watershed "moment" in tennis development. Can you imagine von Cramm imprisoned? What a sad moment of history for man-kind. Excellent article and worthy of inclusion into this series!!

Thanks for the comments. Yes, there is a lot more to say about von Cramm, and that will follow in the series. He was, in fact, only imprisoned for a few months, but he was a 'watched' man by the Nazi regime.

Budge, I suppose, along with the other American players, was in a better position than the European players, though I was surprised at how far into 1939 they were all still touring throughout the world. There was one series in India, as well as lots of venues around the UK—even on boarded-over swimming pools on occasion—that attracted huge crowds. I hadn't realised just what huge draw these players were.

Very well-written piece. When I read A Terrible Splendor last year, so much about Budge reminded me of Sampras, especially in the completeness of their games and the authority in this serves and net play. Budge was one of those guys on whom you could just about bet the house if they were serving for the set or the match.

Very nice piece, Marianne! Sorry it has taken me so long to get to it.

Thanks, Claudia. Just glad to have you back…

Doudoune Canada Goose Prixcanada goose montreal prixcanada goose doudoune manteaux hommescanadian goosecanada goose heli arctic parkacanada goose montreal storecanada goose outlet montrealcanada goescanada goose shopveste canada goose hommenorth facecanada goose parka expeditionveste canada goose femmecanada goose snow mantra reviewcanada goose chilliwack bomber hommedoudoune canada goose prixmonclercanada goose yukon bombercanada goose online shopdoudoune canadaannonce doudoune canada goosemagasin canada goose montrealcanada goose doudoune avisveste canada goose lausannecanada goose on saleacheter canada goosecanadienne hommegant canada goose

yikghhzvyd [url =http://www.ehib.es/sacuinadentia/catala/Hollister.html]Hollister Outlet[/url] qgirvzpotp [url =http://www.casadelaprovincia.es/estilos/Oakley.html]Oakley Baratas[/url] ktuvufarwr [url =http://www.estudioschinos.com/master/Hollister.html]Hollister[/url] oxpeasivmw [url =http://www.svenskahomeopater.se/Documentation/StarterKit/AF.html]Abercrombie Fitch Sverige[/url] dsnsvvnvgw [url =http://www.climovent.com/scripts/CL.html]Chaussures Christian Louboutin[/url] rppwvehiyy [url =http://www.softdata.no/include/_vti_cnf/max.html]nike air max 1[/url] lehqgpprzc [url =http://www.nortrafo.no/editor/templates/free.html]nike free run[/url] rrimzdxqal [url =http://www.fundacionmozambiquesur.org/cache/france.html] Zapatillas Nike Free[/url] cgijriaeyc [url =http://www.imarfer.com/jevamo/fotos/AirMax.html]Nike Air Max 2013[/url] prcderdlvk [url =http://www.plp-spain.com/docu/max.html]Nike Air Max 1 Baratas[/url]

Interesting stuff, I re-designed our blog

and after that the search rankings took a massive

fall

p.s Stay away from the Warrior Forums haha

Thanks for sharing these memories