Todd Martin to Juan Martin del Potro: What’s Missing?

Juan Martin del Potro is a throwback to Todd Martin.

Todd Martin had many of the qualities we ascribed to a top pro in the 1990s. In fact, he had no real flaws in terms of shots, as his return of serve was deadly, his 6’6” wingspan shrouded the net, and his serve was one of the most effective in the game.

In fact, in his autobiography, Andre Agassi described Martin’s serve as being so accurate that he aimed not at the lines, but the edges of lines. Throw in his excellent tactical skills, and Martin was able to serve his way to a pair of major finals and eight titles.

He might well have made more had he been a great mover, not suffered frequent injuries, and his cerebral approach not led to meltdowns in some critical moments in his career. Nonetheless, Martin was a trendsetter in men’s tennis, as one of the first players standing at two meters in height to reach the last round of a major. It took the finest players of his generation – Pete Sampras in the 1994 Australian Open and Andre Agassi in the 1999 US Open – to beat him in the finals he reached.

Ten full years after Martin lost a five-set US Open final – his second appearance in the last round of a major – another 6’6” player named Juan Martin del Potro won his first Open, beating Roger Federer in five sets. Unlike Martin, del Potro’s movement cannot be considered a weak link in his game. Also, based on how he rallied from down two sets to one to win the match, the young Argentine apparently has no mental weaknesses.

Plus, his groundstrokes are bigger weapons than any Martin wielded; big enough to hurt The Great Swiss in a way many hard-hitters before him could not.

But while del Potro can do things that other big men couldn’t, there is one piece missing: the serve. Though five inches taller than Federer, del Potro was outaced 14-8 by the Swiss in that final. It is true that he put 65 percent of his first serves into play, compared to Federer’s 51, and committed just six double faults to Federer’s 11.

This, however, would seemingly indicate that del Potro arrived at a revelation: Not only did he not need to beat Federer with his serve, it was ill-advised to try, and that he would do better to avoid having to hit second serves. With a high first-serve percentage, he could concentrate on doing what he did best: clubbing forehands.

But what if he had felt no such inhibition?

On the whole, the serve is prioritized far less than groundstrokes, particularly the forehand, in today’s game. The serve is still necessary, as it provides players with the chance to move the other man out of position, then allows the server to control the center of the court and dictate play. Players with weak second serves are rare, and those whose second deliveries are vulnerable must put a high percentage of their first serves into play.

While it remains a critical building block in today’s baseline game, the serve is no longer the cornerstone. It wasn’t all that long ago that this was not so.

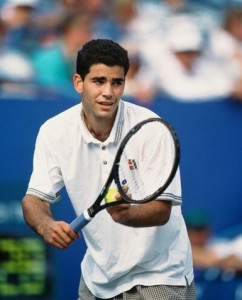

Pete Sampras

In the 1980s a young Pete Sampras made the choice to abandon his two-handed backhand, his best shot at the time, because he wanted to become an attacking player who would win Wimbledon.

During his junior years he struggled, as he was dominated by fellow Americans with less natural ability like David Wheaton and Michael Chang, and this was mostly because of his inconsistency from the backcourt. Sampras, however, was learning how to serve with a relaxed motion that disguised its direction and allowed him to utilize all manner of spins despite using the same service toss each time. Furthermore, he was learning the importance of service placement.

This, plus a newfound determination to reach the net and avoid having to use his newly vulnerable groundstrokes would one day pay off. As he matured, Sampras developed one of the hardest serves in the business, and certainly one of the most varied and reliable. Plus, his groundstrokes became plenty good in their own right, and he eventually emerged as one of the better net rushers of his day.

At around the same time the Dutchman Richard Krajicek was making the same choice Sampras did, one that Stefan Edberg made a few years earlier. Each would credit giving up their two-handed backhand with allowing them to become attacking players, and motivating them develop better serves; a motivation del Potro, with his monster forehand, has apparently not felt.

With surfaces playing faster in those days and racket technology not yet allowing baseliners to hit the edge of a dime on the full stretch with their passing shots, this approach made sense. (And even today, what use would a player like Stefan Edberg have for a two-handed backhand?) By the end of his career, though, Sampras must have felt a little bit like a man out of time.

Marat vs. Goran

Sampras received a hard lesson on the realities of the modern tour in 2000 when Marat Safin, a towering Russian baseliner who oozed with natural athleticism, dispatched him in straight sets in the US Open final.

Marat Safin and Goran Ivanisevic

Safin, at 6’4”, enjoyed a reach only a bit shorter than that of Martin or del Potro. While he frequently blasted serves in the 130 mph range, his wingspan was even more useful with his opponent served. He outaced Sampras 12-8 that day, but this may have had more to do with his return, as the 29-year-old American struggled to get any serves by his strapping young opponent.

As for his own serve, Safin only put in 48 percent of his first deliveries that day, while Sampras’ first serve percentage reached 63 percent. A better percentage simply wasn’t necessary, as the heavy spin on his second serve combined with the accuracy of his groundstrokes combined for an impenetrable line of defense. The free points he won on serve were just bonuses, and Sampras failed to break the Russian even once.

Against an aging opponent using a disappearing playing style this may have been enough, but it wouldn’t always be. Safin’s inconsistency following his breakthrough win is legendary now, but even on pretty good days in the 2004 season he struggled against Federer. In that year’s Australian Open final The Great Swiss turned the tables on the Russian, denying him all but three aces, successfully reading his huge serve and blocking back its pace.

Though the match started close, Federer’s ability to make Safin work a bit harder to hold serve gradually wore down the Russian, and led to a straight sets win for the Swiss.

Much like del Potro now, Safin probably prioritized his groundstrokes as a young player, figuring his hard serve would be good enough if the groundies were clicking.

In many respects Safin has been compared to Goran Ivanisevic of Croatia, who was also 6’4”, had enormous power and a tendency toward racket-breaking. At the heart of their play, though, were fundamental differences, as the crazed Croat’s serve was much, much more than power. Thanks in part to its left-handed delivery and rapid, unconventional delivery, Ivanisevic’s serving accuracy and disguise were a level above the Russian’s.

On his way to his only major title at the 2001 Wimbledon, Ivanisevic demonstrated why in a quarterfinal win over Safin. Each man broke serve only once in the four-set match, and neither faced a break point in the fourth. However, the Croat outaced the Russian 30-14. Safin, with his remarkably clean forehand and backhand strokes, was clearly the better player if the serve came back, but it usually didn’t: Ivanisevic won 89 percent of his first serve points to the Russian’s 78.

Being a lefty, there are certain things Ivanisevic could do with the serve that a right-hander like Safin could not duplicate. Perhaps that idiosyncratic delivery, however, is one that the super-athletic Russian could have developed to make its direction harder to read. Maybe if he’d been trained to make his serve more of a weapon it, coupled with his immaculate returns and innate ballstriking, would have given him a better than 2-10 record against Federer.

The Future

It isn’t just Safin or del Potro, though. Compare today’s biggest players to men of similar height just a generation ago. The 6’5” Tomas Berdych is a far more patient player than fellow six-fiver Krajicek and has one of the hardest forehands of all time. He is, however, nowhere near the 1996 Wimbledon champ in terms of serving.

Tomas Berdych and Richard Krajicek

There are several players aside from del Potro who are 6’6” on tour – Marin Cilic, Victor Hanescu and Sam Querrey most prominently – but only Querrey has what we’d call a serve-centered game. Meanwhile, 6’4” Robin Soderling and Gael Monfils have some serious pop on their first serves, but their accuracy cannot be compared to that of Michael Stich, Mark Philippoussis or Ivanisevic.

Practically the only players in the game today who are known – and feared – for serving are the 6’10” Ivo Karlovic and 6’9” John Isner, men of unprecedented height for tennis players but far from exemplary athletic ability.

My prediction is that the next phase of development in the game will be big men who fuse the best attributes of these players. One day there will be a man of considerable height – between Safin and Delpo, probably – trained from an early age to hit both first and second serves with pace and accuracy, but back it up with great movement and rock solid groundies.

Maybe a player of Safin or del Potro’s talent could do that if taught to, or maybe it takes an even rarer type of athlete like Michael Jordan or LeBron James. Either way, this type of player is the future, and will leave all other types fighting for the runner up slot.

Excellent read! Indeed it appears that once again the tall man wins but only a few will reach the level you predict – then again – there is only room for 1 at the top! Intriguing to think about the future if the boundaries remain the same. Del Potro has not played for so long I have forgotten what he looks like! Wonder when he will return and what kind of shape he will find himself after so long? Of course, the young heal fast and return to form quicker…enjoyed your thoughts, as always…

wonderful read.

I was wondering if you ever thought of changing the design of your blog? Its well written; I enjoy what youve got to say. But maybe you can create a a bit more in the way of content so people might connect to it better. Youve got an awful lot of text for only having one or two photos. Maybe you could space it out better?

Strange , your site turns up with a dark color to it, what shade is the primary color on your web-site?

very interesting.

Excellent site. A good amount of handy details right here. I’m transmitting them to some buddies ans as well expressing with delightful.. 11 Plus tutors And indeed, thank you within your sebaceous!