Miloslav Mecir: The Man Who Could Have Been King of Tennis

You have to admit that there is a huge difference between sultry singing in the shower and performing live at the Met to a packed house filled with critics.

This has implications beyond being able to carry a tune…and being fully clothed.

Besides the necessity of possessing outstanding vocal abilities, you would also need to overcome performance anxieties as you stood in front of an impressive audience thinking it knows exactly what you should be doing—never hesitating to point out your perceived flaws.

The same is doubly true on the playing field.

Monday-morning quarterbacks exist in all fields of endeavor. For example, the tennis player who exhibits all the talent and ability in the world must still overcome his or her own internal jitters in order to win.

This series will highlight tennis players who should have made it to the top of the game but who failed in big moments to win the most critical matches because of (1) nerves, (2) belief, (3) prolonged injury, or (4) the special category belonging to those who won a major but could never repeat the feat.

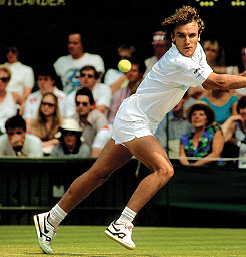

Miloslav Mecir

The “second-best” player who stands out most in my book is the Big Cat, Miloslav Mecir. The Slovak had an uncanny ability to annoy players from all corners of the globe during the 1980s, but he never made it all the way to the top.

Known as the Swede Killer, Mecir chiefly tormented Swedes, especially the renowned Mats Wilander.

Mecir interrupted Wilander’s reign in 1988, the year the Swede won three out of four of the majors and knocked Ivan Lendl off his No. 1 perch. The only Grand Slam Wilander did not win, was Wimbledon, because Mecir defeated him in the quarterfinals in straight sets 6-3, 6-1, 6-3 to Wilander’s utter dismay.

Mecir forever denied the Swede not only an opportunity to seize a Wimbledon crown, but a chance at a calender-year Slam—much like Rafael Nadal did to Roger Federer in 2004, 2006, and 2007.

You have to understand that in the 1980s Sweden was a major force in tennis, led to the summit by Bjorn Borg. Mecir faced Wilander, Stefan Edberg, Anders Jarryd, Joachim Nystrom, Henrik Sundstrom, as well as Kent Carlsson and Jonas Bjorkman during his tenure as a tennis professional.

Mecir confounded opponents with his enigmatic approach to the game. He had no coach, and that disturbed his peers from the outset. They could not understand why the Slovak chose not to retain an adviser and professional teacher.

Mecir also had a poor grasp of English and was pretty much a loner on tour. But he possessed in innate love for the game and respected his opponents in victory or in defeat never calling attention to himself on court, which he considered vain and inappropriate.

The only time I recall that Mecir did retaliate against what he considered bad behavior was during a match in Key Biscayne, Fla., against Lendl. Watch it here.

The Slovak felt honor-bound to behave on court as his parents expected him to behave in public at all times.

Mecir stood a lean 6’3”, and possessed a wicked two-handed backhand that he often unleashed for winners against those serve-and-volley guys who hugged the net. He utilized speed and carefully disguised angles as he glided over the surface of the court.

Mecir always appeared at ease, unruffled—his style characterized as sedate by many commentators. His pace frequently riled opponents who hated to see the Big Cat stalking them across the net because Mecir had an answer for almost everything they threw at him.

The Slovak possessed touch, finesse, and accuracy. Although he was definitely not a “serve and volleyer,” Mecir frequently approached the net utilizing amazing volleying skills. His soft hands could lay the ball down on a dime on the other side of the net wherever there was an unreachable opening.

This quote from Canadian tennis pro Glenn Michibata after he lost to Mecir in Auckland in 1987, sums up how many players felt about playing against Mecir: “Playing him is like bleeding to death.”

He engaged his opponents in long, seemingly free-flowing rallies, lulling them into a false sense of security. Then Mecir would rifle a shot up the line, backhand or forehand, for a winner to end the point, making the player wonder what had happened.

Mecir's defeat of Wilander during Wimbledon in 1988 kept the Swede from a chance at a calendar year slam.

In addition to moving well, while maintaining classic tennis form, Mecir was also excellent on the return of serve. He had the game and the mental acumen to be a winner, but he never captured a major, although Mecir did win an Olympic Gold Medal in men’s singles in 1988, which remained his proudest moment.

Mecir straddled two eras more dramatically than others in the 1980s, when racket technology began to make his beloved wooden racket obsolete as the tennis world gravitated toward graphite. Mecir was the last man standing with a wooden racket as he faced Lendl in the 1986 U.S. Open. No one ever used a wooden racket again in a major final.

Born in 1964, Mecir turned pro in 1982 at the age of 18, making a name for himself by advancing to two ATP finals in 1984. In 1985, he won his first ATP final in Rotterdam, defeating Jakok Hlasek of Switzerland in the final. At the end of 1985, Mecir was ranked just outside the top 10.

In 1986 at Wimbledon, Mecir caught the attention of the tennis world when he took out up-and-coming Stefan Edberg in straight sets. Subsequently, the Slovak lost to Boris Becker in the quarterfinals. But the pinnacle came at the 1986 U.S. Open, when Mecir made the finals to face fellow Czech, world No. 1 Lendl.

The Big Cat, however, yawned that day, losing in a listless effort 6-4, 6-2, 6-0, overcome by the moment.

In 1987 Mecir won six singles and six doubles titles. Lendl and Mecir battled each other frequently, as they advanced through tennis tournaments. They met three times in 1987 with Lendl winning two, including the 1987 French Open semifinals.

Here is another miraculous point of Mecir getting the best of Lendl.

In 1988, after dispatching Mats Wilander in the quarterfinals of Wimbledon with pinpoint accuracy, Mecir was well on his way to dismissing Edberg in similar fashion in the semifinals. Ahead with a two-set lead and even a break of serve in the final set, Mecir could not hold on, as Edberg broke back and took the match.

After winning his Olympic Gold in 1988, Mecir achieved his highest ATP ranking of No. 4 in both singles and doubles.

In 1989, Mecir again made it to a slam final, this one in Australia where he once again faced Lendl. Mecir lost in straight sets, 6-2, 6-2, 6-2. Lendl later explained that he was able to defeat Mecir by hitting deep into the center of the court, robbing the Big Cat of his ability to create his well-disguised sharp angles, which often won matches for Mecir.

Suffering with a back injury and unable to play any longer, Mecir retired in 1990 at the age of 26.

That Mecir never won a major, of course, does nothing to lessen his impact on the game during the eight years he played. Players accorded him high marks on his originality, his creative use of the court, and on the beauty of his game. That he was a frustrating player to meet on court went without saying.

What he could not do, and what many today cannot do, is sustain the high level of his play throughout a tournament. Mecir became a spoiler. He was able to beat anybody on any given day, and that made him dangerous.

But your chances of winning increased significantly if Mecir had won a tough match a day or two before. He did win tournaments, but he never succeeded to win a major.

He lost both his finals to Lendl, who could do exactly what Mecir could not—sustain his high level of play. Lendl expected to win majors and he played to win them, using whatever methods it took to get to the finish line.

No one possessed a finer game than Mecir. If you have not watched him play, take some time to study him because there is much of Mecir in the modern game. He is worth the time to get to know—even if he remains among the best of the second-bests.

[Quote from SI Vault, April 20, 1987—“Miloslav Mecir preys on the game’s top players.”]

Mecir — absolutely my favorite player ever. Those who had little gift for tennis among commentators and viewers/spectator thought he was boring to watch…. He was the master prestidigitator. I tried my darnedest to emulate his game to no avail. But I was wiser for having tried, and I maintain a reputation for unpredictability.

Mecir's biggest flaw was that he just got so nervous — and that mostly because he was/is not self-important, which is kinda necessary for a pro athlete. I can relate to that too. I think of him as the Chopin of tennis — without peer in the salon, but not up to the task in the concert hall.

I recall that Agassi claimed Mecir was his nemesis as well…

You really make it seem so easy with your presentation but I find this topic to be actually something that I think I would never understand. It seems too complex and extremely broad for me. I am looking forward for your next post, I will try to get the hang of it!

We are a group of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our community. Your web site provided us with valuable info to work on. You’ve done a formidable job and our whole community will be thankful to you.

http://realgeekstech.com/?p=853

This is really attention-grabbing, You’re an overly professional blogger. I’ve joined your feed and sit up for searching for more of your fantastic post. Additionally, I have shared your website in my social networks

Its such as you learn my thoughts! You seem to know a lot approximately this, like you wrote the ebook in it or something. I think that you simply could do with some % to power the message house a bit, but instead of that, this is wonderful blog. An excellent read. I will definitely be back.

Odd , your site turns up with a dark color to it, what color is the primary color on your web-site?

I just coulld not leave youir website prior to suggesting that I extremely enjoyed thee standard information a person provide for your guests?

Is going to be again incessantly to investigate cross-check new posts

It’s a shame you don’t have a donate button! I’d without a doubt donate

to this brilliant blog! I suppose for now i’ll settle for bookmarking and adding your RSS feed to my Google account.

I look forward to brand new updates and will share this site with my Facebook group.

Talk soon!

I enjoyed your article on my favorite tennis player, Miloslav Mecir. I learned much about him I didn't know, and you confirmed some ideas about him I had only assumed from watching him play. A commentator once described his look and demeanor as "less a modern professional tennis player and more a renaissance poet."