Americans Love a Prizefight, Even When the Sport Isn’t Boxing

Tennis is one of those rare experiences that can offer that one-on-one contest of physicality, skill, strategy and endurance, and all without the combatants having to get punched in the face. Watch closely enough during this year’s US Open and eventually a match, probably in the men’s draw, will eventually be described using a boxing analogy.

But not all bouts live up to expectations, in the sense that they are not closely fought affairs that teach us about human will. Sometimes one player unexpectedly reaches a plateau where he can’t be touched, and the contest’s outcome is not in doubt.

It’s not dramatic, but it’s still breathtaking.

Drama was what tennis fans wanted to see in the quarterfinal match between Pete Sampras and Andy Roddick in the quarters of the 2002 Open. Residual memory from the previous year’s event, particularly its quarterfinal rounds, was still strong: Sampras and Andre Agassi had played the most commemorated match of their career, a four-set clash of styles that ended in four tiebreaks, neither player having his serve broken. Roddick had taken on fellow young gun Lleyton Hewitt, the eventual champion, on the next night and fallen in a tight five-setter.

A year later, the Roddick-Sampras matchup bore the billing of two American heavyweight servers fighting for survival, and the added selling point of the generational divide: Sampras, age 31, looking for one last slice of Grand Slam glory, while 20-year-old Roddick was seeking to grab his first and live up to his billing as America’s tennis future.

It’s hard to blame anyone who picked Roddick to win that night. He had a far less impressive curriculum vitae than his opponent, but carried a 2-0 record against The Pistol into that encounter and was having a much better season.

Then again, Sampras had fallen to No. 17, so quite a few players were. Sampras’ last major title, his last title of any kind in fact, had come more than two years earlier at the 2000 Wimbledon, where he beat Patrick Rafter to win his 13th Slam and break Roy Emerson’s record. It was a joyous event, followed not long thereafter by his marriage to Bridgett Wilson and firmly established position in game’s history books.

After that historic performance, though, the burden of his nearly 30 years and more than a decade of pro play seemed to weigh on his legs. When coupled with his hereditary thalassemia minor – a condition that regularly results in anemia – this led to a sudden downswing in his results. What’s more, the game at large was changing, as new players emerged and, over the next two years, foisted a series of indignities on the aging champion.

Marat Safin effortlessly deflected his serve at the 2000 US Open finals. Gustavo Kuerten outlasted him at that fall’s World Tour Finals. Roger Federer’s passing shots finally punched one too many holes in his net coverage in the 2001 Wimbledon.

Most embarrassing of these brushes with greatness-in-the-making was the 2001 US Open final. There, Sampras had again beaten Rafter in four sets, won that crowd-pleaser with Agassi, and then avenged his loss to Safin from the previous year. His reward would be a final round encounter with Hewitt, a player whose returns, speed, and passing shots were the stuff of nightmares for serve and volley players even on the best of days; just see his winning records against not only Sampras, but also Rafter and (overwhelmingly) against Tim Henman.

We’ll never know how Sampras might have done had he played Hewitt fresh that day, but less than 24 hours removed from beating Safin he had only one good set in him, falling 7-6 in the first before Hewitt picked him apart 6-1, 6-1.

And that heralded the coming of the worst season of Sampras’ career since the start of the 1990s. He didn’t reach a final in 2002 until Roddick beat him on the clay of Houston. After that, he won just one more clay court match, losing in round one of Roland Garros to little known Andrea Gaudenzi. So palpable was his disappointment that Gaudenzi, who would win $3 million in total career prize money to Sampras’ $43 million, actually felt obliged to console the struggling legend with a conciliatory pat on the shoulder after their handshake.

But the lowest moment of all would have to have been the Wimbledon that followed, when the seven-time champion of the All-England Club won just one round before being sent home by George Bastl of Sweden. The sight of Sampras, sitting in the chair and staring at the grass beneath his feet after the match was probably on the mind of Sports Illustrated’s Jon Wertheim, who during his midterm grades for the event summarized Sampras’ performance thusly: “This isn’t fun for anyone to watch.”

But rather than retire, as many suggested, Sampras was prompted by that final low to adjust: He picked up the phone and rang Paul Annacone.

It was in 2001 that the Pistol had parted with the coach who had shepherded him through the hardest ordeal of his adulthood, the death of previous coach and mentor Tim Gullikson. Annacone’s coaching then helped him complete the breaking of Emmo’s record even as his dominance subsided. Sampras had tried a variety of things after their split, including hiring Jim Courier’s former coach José Higueras to help him gain a firmer hold on clay, but change had done him little good.

In an ever-evolving game, The Pistol most needed a bit of familiarity.

So he and Annacone worked together through the summer, with Sampras stopping his losing skid in Canada and Cincinnati, but accomplishing little more. His last match going into the Open was a three-set loss to Paul Henri-Mathieu in the first round of Long Island.

The lights of New York had much the same rejuvenating effect that they’d shown in the previous year, as he won his first two matches easily. In the third round, though, the huge lefty serve and extensive wingspan of Greg Rusedski frustrated him for five sets, with Sampras seemingly misplacing his forehand return of serve until the very last game.

There he broke Rusedski to end the match, but it was not Sampras’ determination and perseverance that lingered in the Brit’s mind afterwards, it was his legs. ”I’d be surprised if he wins his next match,” said Rusedski. He proceeded to call Sampras a step slow, and added, ”He’s just not the same player from the past.”

In his very next match Sampras would face Tommy Haas, the world’s No. 3 player, who had beaten The Pistol in their three preceding matches, and looked able to fulfill Rusedski’s prophecy. Yet, Sampras won that match in four sets, having never been broken, and setting up his encounter with Roddick.

This looked to be a study of experience vs youthful energy, and of whether Sampras – schooled in the style the great Australians like Laver and Rosewall – was a match for the monster hitting of the young generation even on a good day.

Early in the match, announcer Ted Robinson wondered aloud how Sampras was going to cope with the Roddick serve which, he said, might be even better than The Pistol’s.

“Well,” said John McEnroe, sitting in the booth beside him “it’s harder. I don’t think he places it as well.”

When Roddick served in the second game of the match, and missed on a first delivery, the big difference between the two became obvious: Sampras stepped into the court, carved Roddick’s 100+ mph second serve back and rushed the net. The younger American, for whom passing shots were never a specialty, couldn’t get the pass by his elder compatriot.

When he was the game’s dominant force in the mid-‘90s, Sampras had not been its best pure volleyer; that designation belonged first to Stefan Edberg and then to Rafter, both of whom moved to the net and into volleying position more smoothly than The Pistol and, lacking his forehand weapon, never suffered from confusion as to whether they should stay back of not.

But under Annacone Sampras had continually worked to improve his net coverage and, as his speed and backcourt consistency declined, began going to net behind almost every serve. At times, particularly against Safin and Hewitt, this strategy simply had not worked.

But against Roddick – who slugged and pounded away from the backcourt only to see Sampras absorb the pace of his groundstrokes and transform them into acutely angled drop volleys – geometry and gravity were on his side. He won the match’s first seven points and broke Roddick straight away.

The constant changing in Sampras’ service placement and spins also more than compensated for Roddick’s pace advantage, as he was not broken once that night. By the second set, about the third time Roddick’s serve had been punctured, the great Boris Becker was interviewed at courtside. Having been on the receiving end of a few spectacular serving displays from The Pistol in the ‘90s, Becker was asked what advice he’d have for Roddick.

“Get the hell out of the stadium,” Boom-Boom replied.

This prizefight wasn’t Ali-Frazier. It wasn’t even Ali-Foreman; more like Ali-Liston II. Sampras finished him 6-3, 6-2, 6-4, losing only six serving points in the final set.

The win made him 20-0 in night matches in New York. “You guys say Pete is washed up. I never said it,” Roddick told the press after the match.

At courtside, Michael Barkann of the USA network asked Sampras if the remarks by Rusedski had provided more motivation.

“Who?” Sampras replied.

In the semis, Sampras drew Sjeng Schalken of the Netherlands, whose stiff-as-a-stop-sign serve and flowing groundstrokes took the great American about two sets to figure out. Once he had captured them in tiebreaks, however, he overpowered Schalken in the third. On the other side of the draw Hewitt, who had denied Sampras his last real shot at Grand Slam success, was actually helping to enable this one, as he and Agassi, the only player even older than Sampras in the top 10, had an energy-burning four-set semi.

Agassi eventually knocked the legs out from underneath Hewitt, but for the first time in three years Sampras would enter the USO final as the younger and fresher player.

As a bonus he’d get one more bout with Agassi, but this would not be a repeat of their high-quality encounter of the previous year. Instead, it would be drama of a different kind, as two aging champions fought their own frailties as much as each other.

Sampras’ flat running forehand helped him run out to a set and two-break lead over Agassi, whose legs were still recovery from his semi. Then age started to catch up with Sampras, as he lost one break before closing out the second set, then surrendered the third 7-5. In the fourth, the familiar signs of Sampras anemia were evident, as he slumped over between serves, bounced the ball slowly and more deliberately, and fought to summon serving pace.

Agassi had successfully hit through the effects of the Hewitt match and was now clearly looking ready to go five with his compatriot, who had never been known for his fitness. So, as the set neared its end, Sampras hit out on returns, hoping four of them would hit lines in the same game, and finally succeeding at 4-all. He broke, and the story of how his career would end was all but written.

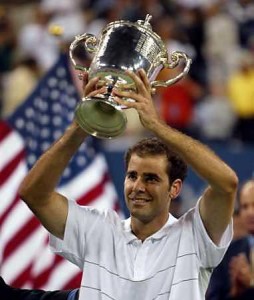

When his first volley at 40-15 moved Agassi slightly out of position, a sharply angled winning volley was the only reasonable thing to expect. It was his 14th major and fifth US Open, tying him with Jimmy Connors and (later) Federer for the most. It would also be his last match on the ATP Tour.

He had not won it for his place in history. He had not won it to set records, or to add to his wealth.

He had won it because he was a tennis champion. Tennis players play tennis matches for a living; tennis champions win them.

He also did it to prove a point: Tennis champions should never be discounted completely.

Epilogue: At the 2003 Wimbledon Rusedski, his ranking having slipped to No. 51 following injury, had a disappointing encounter of his own with Roddick. Rusedski lost in straight sets, but not before the most infamous meltdown of his career (you know, the one where he repeatedly shouted “Well done, well done!” at the umpire).

In his post-match press conference he was penitent, and congratulated Roddick for his win, saying that the young American had a good chance of reaching the semis against fellow rising youth Federer.

Rusedski then quickly added, “But I shouldn’t make predictions anymore.”

That was great when I first read it on Bleacher, but its weathered very well. I think I enjoyed it even better this time, for some reason.

Boxing is one of my favorite sports that I like to read and talk about all the time and you have been talking about the same thing. It was good to have such good things to talk about the boxing game.

Well, its weathered very well. I think I enjoyed it even better this time, for some reason…!

My Recent Post: Top 10 boxing gloves