Review: High Strung: Bjorn Borg, John McEnroe…by Stephen Tignor

Those of us who lived through the final hours of the Borg-McEnroe tennis rivalry in the early 1980s continue to embellish the mystique surrounding those epic matches relying upon imperfect memory and wish fulfillment.

This is because as the matches fade into history, our faint recollection of the events heighten the excitement of each pivotal point recalled.

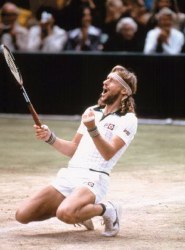

Ultimately when Borg sinks to his knees on the war-ravaged lawn of Centre Court in 1980, we sink into the 3-inch shag carpeting in front of our console TVs exhilarated all over again.

There was nothing quite like their battles waged with wooden rackets during those two turbulent summers when It’s Still Rock’N’ Roll to Me, Workin’ My Way Back to You, and The Boy From New York City were topping the charts and we lip-synched and strutted along with the rest.

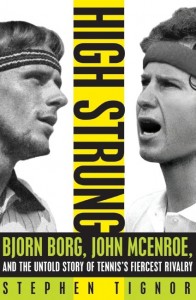

Author Stephen Tignor’s poignant rewind entitled High Strung––Bjorn Borg, John McEnroe, And the Untold Story of Tennis’s Fiercest Rivalry details the denouement and climax of what many consider tennis’ most memorable rivalry.

The opening salvo comes as the brash, loud American teenager meets the cooly, serene Swede on the hallowed grounds of the All England Club in the summer of 1980––where Borg was a God and McEnroe the unwelcome American interloper.

Tignor, with colorful expressive language, mimics the highly rhythmic yet repetitive lyrics of the times. He paints his collage of those days with broad vibrant strokes, detailing most often the Borg-McEnroe rivalry.

Perhaps Tignor retraced their steps in too circular a fashion, lingering a bit too long on their individual paths and their matches; but the author never missed a beat in exploring the depth of intensity as they met twice at Wimbledon and twice in New York City in 1980-1981.

Logically, Bjorn Borg and John McEnroe emerge as the ultimate center of this reflection during an historical period in tennis which culminates with the death of the wooden racket.

But while Borg and McEnroe symbolize the era, there remain other players highly discernible within the bright surface of the story of this epic battle for the top spot in the men’s game.

Tignor brings alive the history leading up to this major shift in men’s tennis built upon the backs of highly regarded amateurs and barely tolerated pros whose reputations were bartered for “play for pay” in school gymnasiums and other hasty arenas. The pros worked hard for their money, and eventually their efforts ushered in the “Open Era.” Open in the sense that now pros were welcome to participate in the large events (the grand slams) and receive compensation for their efforts.

Jimmy Connors, Ilie Nastase, and Guillermo Vilas rode the new tide into the modern era of men’s tennis––receiving a taste of the old but ultimately leading in the new.

Borg, McEnroe, and Vitas Gerulaitis who followed never had to struggle through the professional roadshow that preceded their entrance into the men’s tour. They became the pampered elite often suffering boredom with their schedules––unable to deal with their instant celebrity. The trio led the “me” generation in tennis into the 1980s.

As young men, these tennis stars of the late 1970s and early 1980s found their primary struggles came from immaturity, restlessness and the temptations of fame––better summarized as sex, drugs and rock and roll.

Beneath the celebrity status, however, was a distinct undercurrent of loss. For Connors loss became a crutch for future motivation. For Borg loss loomed as fear for the unknown future and for McEnroe, loss became a wall he had to scale for acceptance.

Tignor points out that Borg became the first superstar of tennis with his good looks and his mystique. He became a marketable commodity and he made millions endorsing products and winning at tennis.

In fact the Swede turned professional as a 15-year old after quitting school in the ninth grade.

The point that comes through Tignor’s energetic prose is that even as Borg built his charisma being silent and stoic, the truth is Borg really had nothing to say. He was only geared toward winning tennis matches which he did with unthinking regularity.

Borg was a master at grinding it out employing mind-numbing drills and falling back on superstitious rituals.

Otherwise, the Swede was running on empty. Just because Borg was silent did not necessarily mean he was deep. Or, so Borg believed. That is what drove him. Winning kept him alive to play again. Winning kept him alive, period.

McEnroe earned his outrageous reputation––every single syllable of it came out of his uncontrolled anger and frustration. He was, indeed, the ugly American and no allusions to Holden Caulfield apply here. The tennis world indulged him, allowing him to be great for a short time. But McEnroe, too, burned out quickly.

This was the era of the paid professional where the winners on tour won big––raking in large payouts in prize money and even more in endorsements. Tennis became an industry and the almighty dollar often directed the game, taking it further away from its days as a gentlemanly pastime.

But tennis also remained singular. You took the court alone and you won or lost based on your physical and mental acumen. There was no “team” except the family and friends who traveled in your entourage. Camaraderie with fellow players was rare although friendships did materialize as was the case with Borg and McEnroe through Vitas Gerulaitis.

While some players could not deal with fame, others could not deal with defeat. Borg could not play if he did not win. McEnroe could not handle the expectations of being World No. 1. Gerulaitis could not handle losing to players not ranked ahead of him and the loss of respect when he stopped winning drove him into dangerous pursuits.

As the era came to an end with Borg walking away from tennis at age 25 and McEnroe peaking in 1984 at age 25, Czech Ivan Lendl won his first grand slam with a metal racket.

Lendl was the future. Borg and McEnroe were the past in a sport where technology continued to evolve the game on the ground and through the air.

With age comes inevitable cynicism about another tennis rewind through 1980-1981 in London and New York. It becomes hard to sympathize with young men who made so much money, winning fame and fortune playing a game.

Ultimately, love of the great game of tennis allows you to celebrate the great wins for McEnroe in 1981 while you agonize over the crushing defeats for the stoic Swede, Borg, who walked out of Flushing Meadows in September of 1981 and out of the tennis spotlight forever.

High Strung details all of the highs and lows as well as the good and the bad in a stylistic retelling of those stories we have heard whispered for decades. Like the tennis itself, Tignor’s retelling is a delicious diversion into one of the best tennis rivalries in the history of game.

The author Stephen Tignor is the Executive Editor of Tennis Magazine. He writes a daily blog on Tennis.com where he has written about the sport for the past twelve years. He lives in New York City.

hey! take a second guess. the nerdiest kid in my high school graduated four years ago he was not cute at all but four years later and he is probably the best looking man I have ever seen, and I’m not just saying that because I get to call him mine, because i know he could have any girl he wanted at this point. brains and brawn,.the best of both worlds.