Olympic Track & Field History: 4 Interesting Sprint Sub-Plots

Doesn’t it seem ironic (and almost cruel) that one of the most heavily promoted, highly anticipated and most-viewed disciplines in all of Olympic track and field is over in a matter of seconds?

If it were a boxing match that ended so quickly after it began, we’d be demanding our money back.

Yet the very essence of the sprint—sheer speed—is its appeal. It’s why we watch, and we accept its brevity without misgivings or regret.

For the athlete and spectator alike, the sprint satisfies one of the three tenets of the Olympic motto: “Citius, Altius, Fortius” (“Faster, Higher, Stronger”).

And though the sprints themselves occupy such a brief moment in time, their residue lives on in the vaults of Olympic history—and often with a surprising backstory.

Let’s enter the vault and take a look.

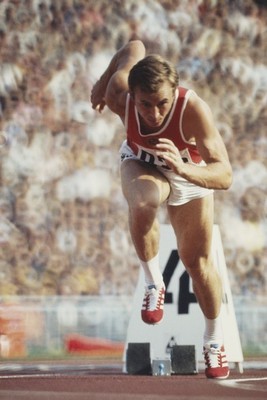

Valery Borzov, Soviet Union, Munich, 1972

The Cold War was still a bit chilly in 1972.

A shroud of mystery separated East from West in Europe, and Americans, too, were curious as to the reports of a steely-eyed Russian who ran with machine-like precision at world-class speeds.

As it happened, America (and the world) got a real good look—at Valery Borzov’s heels.

But this story is as much about who didn’t stand on the podium as who did.

Team USA was led by Eddie Hart and Rey Robinson, who both equaled the world record (9.9 seconds hand-timed) at the 1972 Olympic Trials in Eugene, Oregon. Indeed, the Americans were riding a wave of sprint dominance at the time, and any (non-military) threat coming from behind the Iron Curtain was regarded as little more than a nuisance.

Hart, Robinson and Robert Taylor were on their way to the track for their quarterfinal heats, when they noticed on an Olympic Village TV that the heats had already begun.

They raced to the stadium, but only Taylor—who was scheduled for Heat 3—made it in time to quickly dress down and enter the blocks. Hart and Robinson, assigned to earlier heats and working from an out-dated schedule, were disqualified.

Later in the finals, Borzov, legs churning like pistons, made quick work of the field, taking gold in 10.14 seconds.

Robinson and Hart vowed redemption in the 200-meter dash but the Soviet automaton proved his earlier victory was no fluke, winning the half-lapper in 20.0 seconds.

It was about this time in history when Westerners began to take a hint from the Eastern Bloc nations and sprinting became less an issue of raw speed and more an issue of the science of sprinting.

Gail Devers, USA, Barcelona, 1992 and Atlanta, 1996

Drawing inspiration from an earlier overcomer, Wilma Rudolph, Devers refused to accept that dire possibility and she eventually recovered.

It was a life lesson in positive thinking for Devers which she utilized to make her way to the top of the sprinting world—and ultimately to the finals of the women’s 100-meter dash in Barcelona, 1992.

And she was in good company.

The likes of Irina Privalova (RUS), Gwen Torrence (USA), Merlene Ottey (JAM) and Juliet Cuthbert (JAM) flanked her on the left and right.

In one of the closest finishes in Olympic history—.04 seconds separated the top-five finishers—Devers was declared the winner in 10.82 seconds.

Validating her longevity, Devers retained her 100 gold in Atlanta, 1996.

But the Barcelona story doesn’t end with the 100 gold.

Devers was also an excellent 100-meter hurdler. In fact, she made the finals and was well on her way to her second gold medal when she hit the tenth hurdle and stumbled over the finish line in fourth place.

Today, Devers—recognized as one of the quickest-ever out of the blocks—is paying it forward by passing her wisdom on to the next generation of sprinters.

Peter Norman, Australia ~ Mexico City, 1968

The adjacent photo is iconic in Olympic lore.

It of course depicts Tommie Smith and John Carlos and their famous salute on the 200-meter victory stand at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics.

Given the overriding human rights importance of the incident, it is understandable that several secondary elements of the whole affair have either been forgotten or overlooked.

Perhaps it’s time to dig them up again.

First, let’s remember that Smith’s victory was a world record 19.83 seconds. It was also the first dip below the 20-second barrier.

And how about the forgotten man in the photo—Peter Norman of Australia? Winning silver in an Olympic event is no small matter. In doing so, he set an Australian national record which still stands today—20.06 seconds.

But there is more that Norman did that day.

As a white man, he could not have donned the symbolic black gloves and socks of his counterparts, but he voluntarily stood with them in spirit and wore the OPHR badge they had offered him, Olympic Project for Human Rights.

By doing this, he also paid the same immediate price as Smith and Carlos: banishment from the Olympic team and condemnation from the public and the press.

Though public opinion over the incident did eventually change in America, it was not so quick in coming Down Under.. Norman had hoped to finally be honored with the rest of Australia’s Olympic legends in a ceremony at the Sydney Games of 2000.

He was the only former athlete snubbed.

But the American contingent—notably hurdler Edwin Moses and sprinter Michael Johnson—welcomed him as a hero into their camp.

Norman died of a heart attack in 2006, at 64. Smith and Carlos were pallbearers.

John Carlos spoke of Norman (via BBC News Magazine in October 2008), “Peter didn’t have to take that button [badge], Peter wasn’t from the United States, Peter was not a black man, Peter didn’t have to feel what I felt, but he was a man.”

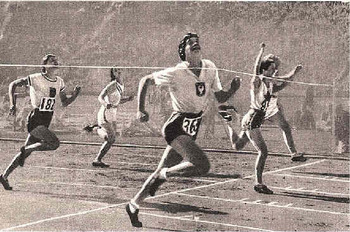

Stella Walsh, Poland ~ Los Angeles, 1932 and Berlin, 1936

Flying under the radar of most 21st century track fans, Stella Walsh was actually one of the most decorated athletes ever. She held numerous national and world records and was an Olympic gold medalist in the women’s 100-meter dash at the Los Angeles Games of 1932.

Born in Poland as Stephania Walasiewics, her name was westernized soon after her family came to America when she was still a very young girl.

For whatever reason, during her athletic prime, Walsh declined to obtain her US citizenship, and competed for her native Poland in all international competitions.

This, combined with an air of detachment immediately before and after competition, did not sit well with her American counterparts, who saw her as being distant, evasive and aloof.

Nevertheless, as a multi-talented athlete, she worked her way up to the elite level, often competing with (and beating) her contemporary, Babe Didrikson.

But it was a young upstart, Helen Stephens who became her most bitter rival. Verbal barbs were commonly hurled back and forth whenever the two met in public.

Between the LA Games of 1932 and the 1936 Berlin Games, the two traded victories on several occasions in head-to-head 100-meter battles.

As happenstance would have it, they met in the 100 finals in the Berlin Games. Stephens beat Walsh, establishing a new Olympic and world record, 11.5 seconds.

Astonished and humiliated, Walsh demanded that Stephens undergo a gender test, saying in effect, “No woman can run that fast!”.

Stephens submitted to the examination and was indeed confirmed to be a woman. In an inevitable changing-of-the-guard, it then became Stephens’ turn to bask in the spotlight.

Many years later in Cleveland, at the age of 69, Walsh was killed as she was innocently caught in the crossfire of an armed robbery.

The ensuing autopsy revealed Stella Walsh—world record-holder and Olympic champion—possessed male genitalia and was determined (through chromosome analysis) to be mostly male, a condition known as mosaicism.

Political correctness aside, she is now often referred to as “Stella the fella”.

Thanks for having a look. One can only imagine the interesting undercurrents London 2012 will provide for future ventures into the vault.

awesome

With a skilled ultrasonographer, two gestational sacs, two embryos and

two distinct fetal heartbeats can be seen six weeks after the first day of the

last menstrual period. After all, they don’t call them guilty pleasures for no reason. Fiber intake

is extremely important, as is water intake and having regular bowel movements.

my page: best hcg drops nz

Even frequent blow-drying at extreme heat or brushing

obsessively can cause your hair to become extremely fragile

causing it to break and fall out. Purchase shampoo or other hair care products that are meant specifically for people with thinning hair.

However, pulling on a scab that was adherent to the skin usually dislodged the graft – often several days after pulling on a hair was

safe.

My web blog: igrow before and after pics

After a quick lunch and a brief nap back at the mobile home, we resumed fishing about three o’clock and fished all the way

until dark. Nowadays, these super coolers are used for both commercial and domestic purpose.

Of course, lots of methods have evolved to try to avoid spooking fish out of your

swim or even stop them from stopping feeding in the possible case of

some line shy fish, and having them leave your swim.

Here is my webpage – marine refrigerator Iphone repair melbourne Florida

When you sign up for HCG wholesale, you are registering for ultimate satisfaction. Additionally, your fat reserves are now being used up.

Dieters are recommended to drink as much water as possible, as the adequate water consumption can help dieters feel more filling and increase their body metabolism.

Feel free to surf to my homepage hcg weight loss guide

These boxes are specially designed for shipping clothes, framed artwork

and perilous materials. Compile Local Menus – We all have our favorite local restaurants that took us months to find and fall

in love with. You can easily find condos, so

there is no need to stay in hotels and lose your luxury beach

experience. You’re going to be able to take part in all of the

conversations; just beware that your cooking abilities are going to be on show, though.

In order to over come this, a telescope in space was necessary.

Carpet cleaning in best can be done through any cleaning machine.

Because of the low cost mode of transportation but more time consuming, there is always a dilemma in picking the right choice.

Systems Administrator career opportunities along with technology Jobs and career are admirable

for well-known image in the field of business. When you are

looking for ways to cut costs, consider turning to Business Electricity Prices to get the best rates.

Now this idea was extended with the time and come in face of banking system.

my page; best small movers cross country

Once there is relief, body can take over and heal itself

by destroying throat bacteria and restoring lining in the

throat that transports the mucus out. Here is what a typical day on our diet looks like:.

I pushed the throttle to idle and allowed the boat to drift slowly.

Feel free to surf to my web page :: Hungry Shark Evolution Hack

Laser treatment can also be used for hair removal, tattoo removal

and to treat scars or hyper pigmentation. How do shooting is getting worse,

falls into folds and the chin line to create an area

of the jaw, jaw lines, marionette. Information You Should Know

About Plastic Surgery is another excellent instance of this.

Visit my blog … nose job under local anesthesia

I was enjoying this game. I was enjoying it for some time.

Last update destroyed a lot of things for myself and I ledft it…

Is this a blog series? If not, it should be. I would love to read the next installment on this subject.

Shared! Shared! This is AWESOME stuff man! Thank you!

Blog da Timberland: E, para encerrar, qual é a relação de você com a Timberland? Usa nossos produtos em suas viagens? Quais?

timberland with gold logo

Hey,

Thanks share this type article on this site,they are more useful to their on site,I think you are manage by them work to understood peoples so you grate work to wrote this article so keep it up i read your bog every time..

Exceptional submit online order. I became examining frequently the following site with this particular inspired! Useful details precisely a final aspect 🙂 I actually preserve this kind of details a good deal. I’m trying to find this particular data for your very long time. Appreciate it and also regarding success.

Handy data Santorros Carvar. Fortunate us I uncovered your web site unintentionally, and i’m shocked the key reason why this specific coincidence wouldn’t occurred beforehand! I personally added the item.

It’s also possible to TWICE FOR LESS where you

can put-up any sum significantly less than your first bet.

There exists a lot regarding value in a office washing company in which promises and also reinforces environmentally friendly cleaning. Nonetheless, one factor is encouraging, and a really different you are actually discussing the discuss and jogging the wander. Here is a listing of the points you must supervise so that you can confirm your office washing services are really green purifiers. As you will observe, the undeniable fact that you utilize commercial washing services will not mean you don't need to keep an eye fixed face to face being completed: