Doesn’t it seem ironic (and almost cruel) that one of the most heavily promoted, highly anticipated and most-viewed disciplines in all of Olympic track and field is over in a matter of seconds?

If it were a boxing match that ended so quickly after it began, we’d be demanding our money back.

Yet the very essence of the sprint—sheer speed—is its appeal. It’s why we watch, and we accept its brevity without misgivings or regret.

For the athlete and spectator alike, the sprint satisfies one of the three tenets of the Olympic motto: “Citius, Altius, Fortius” (“Faster, Higher, Stronger”).

And though the sprints themselves occupy such a brief moment in time, their residue lives on in the vaults of Olympic history—and often with a surprising backstory.

Let’s enter the vault and take a look.

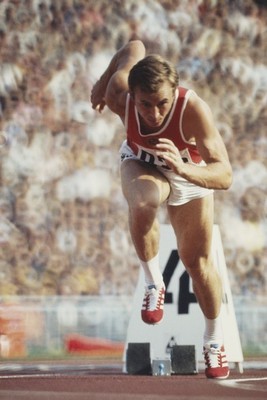

Valery Borzov, Soviet Union, Munich, 1972

The Cold War was still a bit chilly in 1972.

A shroud of mystery separated East from West in Europe, and Americans, too, were curious as to the reports of a steely-eyed Russian who ran with machine-like precision at world-class speeds.

As it happened, America (and the world) got a real good look—at Valery Borzov’s heels.

But this story is as much about who didn’t stand on the podium as who did.

Team USA was led by Eddie Hart and Rey Robinson, who both equaled the world record (9.9 seconds hand-timed) at the 1972 Olympic Trials in Eugene, Oregon. Indeed, the Americans were riding a wave of sprint dominance at the time, and any (non-military) threat coming from behind the Iron Curtain was regarded as little more than a nuisance.

Hart, Robinson and Robert Taylor were on their way to the track for their quarterfinal heats, when they noticed on an Olympic Village TV that the heats had already begun.

They raced to the stadium, but only Taylor—who was scheduled for Heat 3—made it in time to quickly dress down and enter the blocks. Hart and Robinson, assigned to earlier heats and working from an out-dated schedule, were disqualified.

Later in the finals, Borzov, legs churning like pistons, made quick work of the field, taking gold in 10.14 seconds.

Robinson and Hart vowed redemption in the 200-meter dash but the Soviet automaton proved his earlier victory was no fluke, winning the half-lapper in 20.0 seconds.

It was about this time in history when Westerners began to take a hint from the Eastern Bloc nations and sprinting became less an issue of raw speed and more an issue of the science of sprinting. Read the rest of this entry →

Being a sports fan comes with passion, dedication, heartbreak, and ecstasy. It is a lifestyle littered with the unpredictable. But no matter who you support or what sport you play, there is one thing all sports fans can agree on; live events always offer up the best experiences you’ll ever be apart of. That’s why we have compiled a list of some absolutely must-have experiences every sports nut should soak up in person, with your own eyes; your heart beating so hard you can see it through your shirt.

Being a sports fan comes with passion, dedication, heartbreak, and ecstasy. It is a lifestyle littered with the unpredictable. But no matter who you support or what sport you play, there is one thing all sports fans can agree on; live events always offer up the best experiences you’ll ever be apart of. That’s why we have compiled a list of some absolutely must-have experiences every sports nut should soak up in person, with your own eyes; your heart beating so hard you can see it through your shirt.