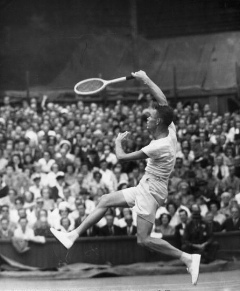

Great Men of Tennis: “Jack” Kramer, Father of the Modern Game

![]()

John Albert Kramer, better known as Jack Kramer, did more than play a mean game of tennis.

He initiated a style of play more reminiscent of the serve and volley of John McEnroe than of Pete Sampras––though both games reflect the prowess of Kramer on court.

Off court, Kramer forced the evolution of the structure of modern tennis. He drove the bus that finally arrived in 1968 when amateur and professional tennis blended into one tour, finally allowing players to gain control over their own careers.

The Beginning

“Jack” Kramer was born on August 1, 1921 in Las Vegas, Nevada, and died September 12, 2009 at the age of 88. His father worked for the Union Pacific railroad. Naturally, the family never accumulated the finer things of life as resources were always lacking.

Shortly after Jack was born, the family moved to the Los Angeles area. But young Kramer had natural athletic ability. He soon found his way into tennis after the family moved to the San Bernardino area, where Kramer was privileged to watch a match played by the great Ellsworth Vines. He became inspired by the brilliant play of Vines and dedicated himself to playing tennis.

Amateur Career

Without much money, Kramer still received excellent tutelage under the supervision of legendary teachers Dick Skeens and Perry T. Jones of the LA Tennis Club. During a successful “junior” career, Kramer, a natural right-hander, became the Boys’ National Champion in 1938.

In 1939, Kramer was selected to team with Joe Hunt in the United States Davis Cup tie with Australia. Kramer became the youngest player ever to compete in a Davis Cup final––a record he held for 29 years. The U.S. lost that tie, and finished as the runner-up in 1939.

With the outbreak of the second World War, Kramer joined the United States Coast Guard. He still continued to participate in U.S. tennis events, though, winning prizes for his participation––especially his doubles play, which earned him a Top 10 ranking in the U.S.

After the war, however, Kramer began his tennis career in earnest.

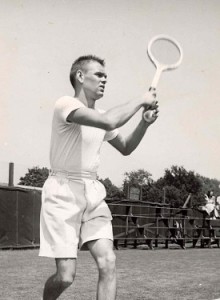

Kramer played an aggressive serve and volley game, coming in after almost every first serve, especially on grass and cement. He developed the game in the 1940s that John McEnroe played in the late 1970s and 1980s.

Kramer moved forward into the court to meet the ball, forever denying his opponent adequate time to react––taking short balls and second serves and punishing the person on the other side of the net with fast-paced play and accurate and deadly ground strokes.

But aggression was reserved foremost when Kramer was serving. His rule was that you held your serve at all costs and then played the percentages on your opponent’s serve.

It became of matter of efficiency––you saved your energies and used them when your chances to win were the greatest. These theories he expounded in The Game: My 40 Years in Tennis![]() ,* where he talks about his “Big Game” strategies, its foundation, growth and practice.

,* where he talks about his “Big Game” strategies, its foundation, growth and practice.

Kramer dominated after the War, winning the U.S. National Singles Championship in 1946 and 1947––what we now call the U.S. Open. Kramer won Wimbledon in 1947 as well. It is widely reported that he should have won the Wimbledon title in 1946, except that he developed blisters on his right hand, which severely hampered his ability to play his game.

He won the equivalent of the U.S. Open Doubles four times in 1940, 1941, 1943, and 1947, as well as Wimbledon doubles in 1946 and 1947. Kramer also won a U.S. National Mixed Double Titles with Sarah Palfry Cooke in 1941.

Add to those impressive results the fact that Kramer won all six singles Davis Cup matches playing for the U.S., leading the U.S. team to victory in 1946 and 1947.

Professional Career

Before 1968, very few tennis players controlled their own destinies.

They were accorded the status of amateurs, in which case they supposedly received no money for participating in tennis tournaments like Wimbledon, the French, the U.S. and Australian Championships, as well as other sanctioned national or state events like the Italian Open or the Canadian Open (now called the Rogers Cup).

![]() This, of course, was not strictly enforced and players received funding under the table, so to speak, for travel and other expenses. As amateurs, they were under the control of national or international federations that could decide not to send them to specific events.

This, of course, was not strictly enforced and players received funding under the table, so to speak, for travel and other expenses. As amateurs, they were under the control of national or international federations that could decide not to send them to specific events.

The problem was that in order to make enough money to live, the best players turned professional, where they generally were under contract to a promoter who arranged their schedule.

Once a player turned pro, he or she could not compete in amateur sanctioned tennis tournaments. They could no longer play, for example, at the Wimbledon Championships or the U.S. Nationals––because they were not allowed and because they had to go where their promoters sent them.

Like many of his contemporaries, Kramer turned professional in 1947 because he needed the money. He could no longer play just for the glory. Like Rod Laver, Ken Rosewall, and Pancho Gonzales, along with most of the biggest names in tennis––the best players were not competing in the Slams.

Kramer became the United States Professional Champion in 1948 and led the professional field from 1948 through 1953. He overtook Bobby Riggs and became a main draw on the pro tour. When his arthritic back would no longer allow Kramer to compete, he took on the chore of being a promoter––which he continued for a decade. ![]()

The Open Era

It was obvious to Kramer that the current system in tennis was untenable.

He pushed hard to merge the amateur and pro tours so that tennis could flourish.

Without the big names, the prestigious tournaments were losing out. Without the prestigious tournaments, the big names in tennis were losing exposure and deserved fame.

Kramer could see that and pushed hard.

He fell short in 1960, but finally succeeded in 1968. The first Grand Slam tournament to go “open” was the 1968 French Open. It was Kramer’s drive and determination that made this happen.

Kramer was also the person who devised the accumulation of points and year-end championships––initiating a series of variations on this concept from 1970 forward. Regardless, the point system as devised by Kramer has remained pretty much intact.

Additionally, Kramer began the ATP (Association of Tennis Professionals) which exists yet today. His contributions to the game of tennis were remarkable, always insightful and forward-looking.

But perhaps most people today remember Kramer as a tennis commentator for the BBC and the U.S. Open Championships. His television analysis of tennis matches was marked by his easy manner and the depth of his knowledge about the game.

He conveyed the often complex nature of the match to his television audience, enlightening and entertaining them at the same time. He served as a commentator for the BBC for 14 seasons in the 1960s and 1970s until the ATP voted to boycott Wimbledon when tennis colleague Nikki Pilic was suspended by the ITF.

When the All-England Club upheld the suspension, and after supporting the boycott as President of the ATP, Kramer became persona non grata at Wimbledon.

Without a doubt, Kramer was the most influential man in tennis in the 20th century, and he is responsible for the huge surge in the sport’s popularity after 1968. His influences were so many and so varied, it is hard to do them justice in the limited space this article provides.

Much is written about the man, and understanding the past in tennis helps mightily in understanding a modern dilemma—why it is impossible to compare present and past players based on their records.

Jack Kramer remains the Father of Modern Tennis.

*Excerpt from The Game: My 40 Years in Tennis by Jack Kramer with Frank Deford, 1979, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, NY

[Cliff] Roche’s first rule of percentage tennis was to hold your serve… It didn’t make any sense to go running all over the court trying to break the other guy’s serve, if this left you too tired to hold your own serve. Priorities. Percentages.

![]()

So, what Roche taught me was to play it easy against the other player’s serve until he fell behind love-30…Statistics show that on a fast court, a good server will hold serve more than 50 percent of the time even after he is down love-40. So early in a set I let a guy have his serve unless he got behind love-30 or love-40 off his own mistakes. I would just try and keep him honest–go for winners off his serve, try something different–whatever I could do with the least loss of energy. Then when it got to 4-all, I played every point all out (except possibly if he got ahead 30-love or 40-love on his serve).

…Roche taught me to play it even safer if you were serving the odd games. The guy who serves the even games serves after the break when he is rested and has had a chance to dry his hands.

When I won my first Forest Hills [US National Championships] against Tom Brown in 1946, Roche was in the marquee. The first set was a toughie. I won 9-7. Then I went up 5-2 in the next set. Here was a perfect time for a kid to lose his head and go for the break. You’re so close to 6-2, two sets to love, you can taste it. But for what purpose: you fail to break him; he’s 5-3, you’re tired, your hands are sweaty, he’s got a good chance to break you, and then he’s got a rest and dry hands before his serve. Boom, like that: 5-5.

I let Brown have the game for 5-3 without a struggle. Then I looked up and saluted Roche, and he nodded back. It was as if I were saying: “I lost that one for you.” And my energy spared, I served out the set at 6-3 and then closed out the match at love.

If you enjoy looking at the foundations of the game of tennis, please read others in this series “Great Men of Tennis” by JA Allen, Marianne Bevis and Claudia Celestial Girl. You might also wish to check out our series on “Queens of the Court.”