Clemens’ Mistrial is Perfect Ending to Baseball’s Steroid Era

Given that the “Steroid Era” in baseball has been built on a series of lies, accusations and uncertainties, it seems almost normal for baseball’s darkest era to come to an end with a mistrial in a federal courtroom that accomplished nothing and left as many questions as answers.

Ever since baseballs started flying out of stadiums at uncanny rates beginning in the early 1990s, the game of baseball has been in a civil war between those who believe in preserving the history and sanctity of the sport and those who saw the opportunity for greater success through artificial means.

This battle has left baseball with nearly two decades of inflated statistics and history that no one really knows what to do with.

Baseball purists have always pointed to the purity of statistics as being one of the components that make baseball special. For generations they contended that you could directly compare the statistics of players like Joe DiMaggio, Tris Speaker and Lou Gehrig with Hank Aaron, Willie Mays and Sandy Koufax to legitimately determine the greatest players of all-time.

Now in reality that argument is unsupportable as each era has its own nuances that make it difficult to compare with other generations.

Frank “Home Run” Baker earned his nickname by leading the American League in home runs four consecutive years between 1911 and 1914. During those four seasons, he blasted a combined total of 42 home runs, including 9 to lead the league in 1914. Yes, NINE! He finished his 13-year career with 96 home runs and 103 triples.

Just a few years later, a giant lefthander pitcher named George Herman “Babe” Ruth switched from being one of the American League’s most dominant pitchers to being its greatest slugger. He led the AL with 11 home runs in just 95 games in 1918 and in his first full season playing in the field in 1919 set a new single season record with 29 home runs. He hit 54 home runs in 1920 and 59 the following year and in 1921 became MLB’s career a home run leader, a distinction he would hold until 1974.

Should the Government Continue Their Case Against Roger Clemens?

- No, is a waste of time and money (75%, 18 Votes)

- Yes, justice must be served (25%, 6 Votes)

Total Voters: 24

The great players of the first four and a half decades of the 20th Century compiled impressive statistics playing in a league that didn’t allow some of the best players of the era to even compete. While Ruth, Gehrig, Ty Cobb, Ted Williams, Rogers Hornsby and others were great players, how might things have been different if Josh Gibson Satchel Paige, Ray Dandridge, Cool Papa Bell and the other stars of the Negro League had been able to show their talents?

Expansion and relocation in the 1950s and 1960s also changed the game as suddenly travel became a greater part of baseball. Instead of traveling primarily by train and going no further west than St. Louis, baseball players had to adapt to plane trips to places such as Los Angeles, Houston and Seattle.

After pitchers dominated the game in 1968, the pitcher’s mound was lowered to its current height of 10 inches above home plate (from 15 inches). The result was an increase in the league batting average from .237 in 1968 to .248 the following year and an increase in the average number of home runs per team from 100 to 130.

So, while baseball purists can argue that the Steroid Era has greatly skewed the ability to compare eras, I’m not sure that argument ever was as supportable as some would argue.

However, there is no question that the steroid era, along with other factors including the changing dimensions of baseball stadiums and the continued dilution of pitching talent through expansion, suddenly changed how players were judged and valued and that is something that baseball is struggling with today.

There was a time when hitting 50 home runs in a season was one of the greatest accomplishments of a baseball slugger and among the rarest of baseball feats.

From 1920 when Babe Ruth became the first to eclipse the 50-home run mark, through 1990 when Cecil Fielder blasted 51 homers, the milestone was reached 18 times by 11 different players. The most home runs in a season during that time was registered by Roger Maris, who in 1961 hit 61 home runs to pass the record of 60 home runs established by Ruth in 1927.

Since 1995, the 50-home run mark has been reached an astounding 24 times by 15 different players. Three players, Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa and Barry Bonds each had seasons where they eclipsed the seemingly unobtainable total of 61 home runs. Bonds now holds the single season record of 73 while McGwire blasted 70 home runs in 1998 and 65 the following year. Sosa is the only player to hit more than 60 home runs three times as he hit 66 in 1998, 63 in 1999 and 64 in 2001.

One of the long-lasting side effects of the Steroid Era will be the distrust and skepticism now routinely thrust upon any player who approaches big power numbers.

Unlike the previous era, when eight of the 11 players to reach 50 home runs in a season eventually became Hall of Famers, it is very doubtful that most of the players who have reached 50 home runs in a season since 1995 will ever gain election into the Hall of Fame.

While Ken Griffey Jr. has never been implicated in steroid use and should be a first ballot Hall of Famer, many of the others who have reached the 50-home run mark, including Bonds, McGwire and Sosa, have been identified as likely users of steroids, regardless of whether they have ever actually tested positive.

Jim Thome, who hit 52 home runs in 2002 and is just five home runs short of 600 for his career, has never received the accolades that you might expect for someone with his gaudy statistics and may not be an automatic Hall of Fame choice even though he also has never been labeled among the likely steroid users.

Even now that testing for performance enhancing drugs has been in place since 2004 and overall home run totals are back to levels of the pre-steroid era, there are still players who break out with a special season and a now skeptical baseball world is having a difficult time knowing exactly how to handle such players.

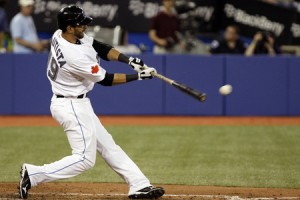

Every time a player like Jose Bautista has a breakout season the question of whether they used steroids is inevitable.

Such was the case in 2010 when Jose Bautista came from nowhere to slug a league-leading 54 home runs. Considering that in 2004 he played for four different teams and prior to 2010 had not hit more than 16 home runs in a season, he fits the classic profile of players from the Steroid Era where sudden power surges were very common.

However, Bautista has credited his sudden power surge with a swing change late in the 2009 season and given that drug testing has been in place throughout his career, it seems unlikely that Bautista has used artificial means to suddenly become the leading power hitter in baseball.

Yet the challenge that Bautista and future sluggers face is in how to quantify their success. Is reaching 50 home runs back to being a cherished and special total? Or for future sluggers to gain attention do they need to challenge for the mark of 61, 70 or 73?

For the last several years, many baseball fans have been hoping that there would eventually be that one seminal moment when all the facts about the Steroid Era would come to life and clarity for how to deal with the records from that time would be found.

The hope in 2008 was that the Mitchell Report would serve as that ultimate document that brought a close to the era and finally gave clarity to who had been involved and what they had gained.

Instead, what former Senator George Mitchell spent 21 months investigating the sport, yet was stonewalled at almost every turn by players and baseball personnel who had no interest in voluntarily sharing just how widespread steroid use had been in the game.

The only people willing to name names were a former clubhouse worker for the New York Mets who was under federal indictment and a former trainer that had worked for both the Toronto Blue Jays and the New York Yankees.

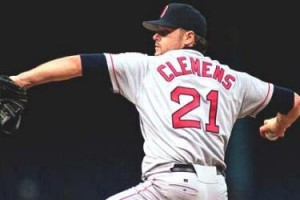

Between 1986 and 1992, Roger Clemens was the best pitcher in baseball, but he struggled during his final four seasons in Boston.

Ultimately, only 89 players were named in the report and it was obvious that while several big names were included, the report fell far short of being the comprehensive report that could be considered a complete list of all that had been involved in using steroids.

One of the players named in the report was former pitcher Roger Clemens, who had worked extensively with the former trainer Brian McNamee.

Even before the Mitchell Report was released, it didn’t take a brain surgeon to surmise that Clemens had probably used artificial means to rebuild his career.

A five-time All-Star, three-time Cy Young Award winner and one-time league MVP during 13 seasons with the Boston Red Sox, it appeared that his career was nearing an end when the Red Sox decided to let him go following the 1996 season.

At the time, it seemed like the right decision. After averaging a 19-9 record, 239 strikeouts and a 2.66 ERA between 1986 and 1992, his numbers dropped to averages of a 10-10 record, 179 strikeouts and a 3.77 ERA from 1993 to 1996.

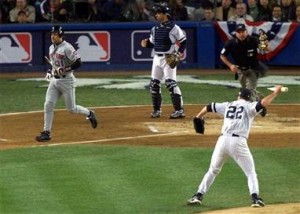

But suddenly, after signing with the Toronto Blue Jays as a free agent in 1997 at the age of 34, Clemens reverted to past form and over the remainder of his career was consistently one of the best pitchers in baseball.

He won the Cy Young Award in both 1997 and 1998 with the Blue Jays and then another with the New York Yankees in 2001 at the age of 38. But the most amazing season during the second half of Clemens career occurred in 2004. After originally announcing his retirement following the 2003 season, he decided to come back with his hometown Houston Astros in 2004 and at the age of 41 claimed his seventh Cy Young Award with an 18-4 record and 2.98 ERA. The following season, he went 13-8 and led the majors with an ERA of 1.87.

Those numbers were unusual for a 30-year-old during the Steroid Era, but were particularly out of the norm for a 42-year-old.

So following his inclusion in the Mitchell Report, most baseball fans weren’t extremely surprised.

However, unlike others named in the report who acknowledged that they had used PED’s at some point, Clemens was adamant that he was being framed.

He went so far as to insist on testifying before Congress. An act that many at the time thought was a waste of time for Congress and for baseball.

So, in front of a House of Representatives panel where many members spent as much time patting him on the back as they did asking him questions, Clemens got his chance to tell the world that he had never used steroids. He also spent most of the day throwing his friends and family under the bus.

Clemens claimed that packages of PEDs that were sent to his house were actually for his wife. Then he said his former teammate Andy Pettitte “misremembered” conversations where Clemens had supposedly told him that he was using steroids.

But Clemens was not the only person providing testimony under oath. His old trainer, McNamee, testified that he had provided steroids to Clemens as well as Pettitte and other Yankees.

On that day it looked like Clemens had gained the closure he desired, but it turns out that it was just beginning.

Clemens and McNamee traded defamation lawsuits with Clemens’ suit against his former trainer eventually being thrown out of court.

More than two and a half years after the hearing, Clemens was indicted for lying to Congress.

You can debate all day whether the government should have been spending millions of dollars to pursue the criminal case against Clemens, but for both Clemens and those who were hoping for some closure to the Steroid Era, this case seemed to be the best hope.

That was, at least, until the prosecuting attorneys pushed the envelope a bit too far and ended up with a mistrial that many hope will mark the end of this government expenditure.

The result was a lot like a baseball rainout, leaving everyone with unfulfilled expectations and no final outcome.

Clemens, who could argue that a not guilty verdict would finally vindicate him, is left with a case of good news-bad news. The good news is that he will likely not go to prison. The bad news is that he may spend the rest of his life under the cloud of steroid suspicion.

A hearing in early September will determine if Clemens will face a new trial, but many hope the government will see the writing on the wall and walk away from the case before it costs more money and time.

Clemens is still facing a defamation suit by McNamee that could provide some interesting results, but with the stakes much less than a potential prison term, it may not be quite as scintillating as the criminal trial surely would have been.

To some fans, the Steroid Era and many of its stars will always be the black sheep cousins that everybody knows about, but no one wants to discuss. However, as time goes by it will become a blip on the radar in the long timeline of baseball history.