The Harlem Globetrotters: Basketball’s Ambassadors of Fun

The Harlem Globetrotters began in Chicago as the "Savoy Big Five."

When Professor James Naismith nailed that peach basket to the wall in 1891, he couldn’t have imagined the popularity his invention would someday enjoy around the world.

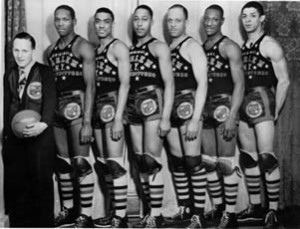

When promoter Abe Saperstein gathered five poor inner-city kids from Chicago’s South Side to play some serious basketball in 1926, how could he have known the destiny of fame and goodwill that would one day materialize?

The six-foot Naismith and the five-foot Saperstein; astute academian and absolute comedian; oil and water, fire and ice. As individuals, they were almost polar opposites.

But when the brainchild of the professor and the vision of the promoter happened to cross paths, something magical and enduring and beyond anyone’s wildest dreams was set in motion.

When evaluating success, it is often useful to look to the past. Hindsight offers a great perspective on the turning points, opportunities, happenstance and even the mistakes which all contributed to the positive outcome.

With that in mind, let us trace the course of basketball in general and its intersection with the path of its greatest proponent, the Harlem Globetrotters.

Basketball was an almost instant success after its inception. Within five years, intercollegiate competition was organized. Semi-pro tournament teams began to appear as the demand for the fast-paced, fan-friendly game increased. These early teams would tour the eastern United States, barely surviving on their meager cut of the gate receipts.

By the mid-1920s, there were several leagues playing in the major cities of the East.

The early forerunner to the NBA was an all-white league, which often struggled to find quality players and fill seats. Meanwhile, the black leagues were packing the house, yet not realizing the financial compensation and social status of the elite pro league.

It was in this segregated environment that the Jewish entrepreneur, Abe Saperstein, put together his all-black quintet in the South Side of Chicago. They were called the Savoy Big Five after the Savoy Ballroom where they played their home games.

Due to financial constraints, Saperstein served as coach, manager, trainer, chauffeur, dishwasher, and first-and-only substitute off the bench. The comical sight of the waist-high, pot-bellied businessman playing in the land of bean-pole giants was a portent of things to come.

Despite Saperstein’s casual, almost comical persona, the man understood the finer points of talent and promotion. He changed the name of his team to the Harlem Big Five to stress the image of an all-black team—although it would not be until 1968 that his famous team even played a game in Harlem, New York.

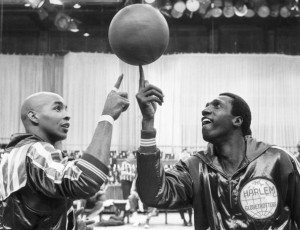

After originally playing serious basketball, the Globetrotters recognized that their niche was as basketball showmen. Goose Tatum was one of their great front-men.

In order to portray the suave image of world travelers (although they hadn’t yet ventured beyond the Midwest), Saperstein dubbed his club the Harlem Globetrotters. Thus, in the finest tradition of the consummate promoter, P.T.Barnum, he prophetically, if not accidentally, marketed his team for the future.

The Globetrotters were so talented and successful as a team they almost “won” themselves out of a job. They compiled season records of 101-6, 145-13, and 151-13 in their first three years.

They so dominated the league that willing opponents were becoming increasingly difficult to find. On one occasion, the Globetrotters were beating their “victim” 112-5. The crowd was becoming bored and started to leave early.

In one of those moments of heaven-sent brilliance, Saperstein stepped into his destiny.

He ordered his players to lighten up a bit, clown around a little, do the razzle-dazzle thing—like in practice.

The fans returned to their seats.

Although the game officially ended as a blowout, the spectators left with a smile, having gotten their money’s worth and more.

The comedic, slapstick routine became a regular part of the Harlem Globetrotters’ game. The combination of quality basketball and showmanship filled the arenas and cranked the turnstiles wherever the traveling troupe played.

Saperstein’s Globetrotters began to turn a profit. They also began to turn heads at the highest levels of basketball. The early 1940s were dominated by the boys from Chicago. They won the prestigious (black) World Basketball Championship and two International Cups.

They sold out arenas, developed a faithful fan base and seemingly were on top of the world.

Their course appeared to be charted.

But one ugly obstacle remained in their path: because of the color of their skin, they were still not allowed to play in the one professional league that mattered.

It was inevitable that the NBA would finally catch wind of the rumblings in the semi-pro leagues by teams such as the Globetrotters and the New York Rens. In 1948, Saperstein and the NBA worked out a deal. The Harlem Globetrotters would go up against the Minneapolis Lakers, the NBA’s best, in an exhibition game.

Speculation and anticipation ran rampant as basketball fans across the land wondered how a team of comedian/entertainers would fare against the reigning NBA champs.

A record crowd watched, as it quickly became apparent that this was going to be a grudge match—but not because of race. The Lakers, not wanting the embarrassment of losing to a team of clowns, brought their best game. The Globetrotters quickly realized the quality of their opponent and sidelined their antics.

In a hard-fought, back-and-forth game, the Trotters prevailed, 61-59.

The Lakers wanted a rematch and another exhibition game was set up the following year. The Harlem Globetrotters confirmed their legitimacy as an NBA-caliber team in a 49-45 win.

The NBA’s color line was now on shaky ground.

Regrettably, it was not yet a sense of decency but one of financial expediency which forced the league to reconsider its racial policies.

The very next year, Charles “Chuck” Cooper, drafted by the Boston Celtics, was the first black man to set foot on an NBA court. Soon to follow were the likes of Earl Lloyd and Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton.

Saperstein, a noted advocate of minority causes, was of course delighted that his team played such a large role in the integration of basketball. But it was a double-edged sword. Very quickly, the NBA began to draw the most talented black players and within a decade the semi-pro leagues all but vanished.

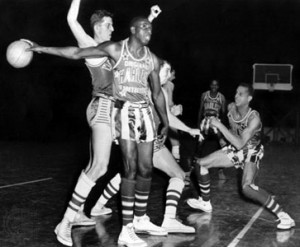

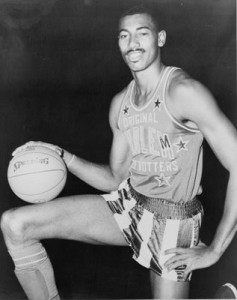

Wilt Chamberlain made his mark with the Globetrotters before unleashing his skills on the NBA.

As the NBA began to prosper, the Globetrotters were losing their best players to the pro draft. Future stars like Clifton, Wilt Chamberlain and Connie Hawkins stopped off first with the Harlem Globetrotters on their way to great careers in the NBA.

But Saperstein made lemonade out of lemons. He refocused his team on clowning, tricks, and jokes—and took the Globetrotter name literally. Travel abroad became a staple in their schedule.

Then, all across the globe, many people got their first exposure to James Naismith’s wonderful game—with a comical twist of course.

The Trotters never really lost their popularity with the expansion of the NBA—in fact, it increased. They became known more as entertainers than serious competitors, but the post-war world seemed ready for the likes of a Meadowlark Lemon and a “Curly” Neal.

The Globetrotters reached their greatest fame in the 1970s led by Curly Neal and Meadowlark Lemon.

Through the decades since, the Globetrotters have played more than 25,000 games in 118 countries, bringing goodwill and laughter to over 200 million people—all while promoting the game of basketball.

Posthumously, Naismith and Saperstein were both inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame.

The inventor and the innovator brought just the right ingredients to make an already fun game into something special. With a little imagination, one can almost envision the two looking down at their successful collaboration, engaging in a heavenly high-five.

Given today’s high profile players and Madison Avenue marketing, it would be understandable if the reader pointed to a particular player or team as a reason for loving the game.

It would even make sense if one justified his affection for the game by citing “family tradition.”

But way down deep, in the core of your sporting soul (or at least, in your funny bone), you know—yes, you know…the Harlem Globetrotters made you love basketball.

~ ~ ~ ~

Fun Fact

Michael “Wild Thing” Wilson, a current Globetrotter, recently set a Guinness World Record by dunking a basketball through a hoop measured at 12 feet above floor level. In regulation basketball, the basket is ten feet high.

Watch video