Remembering The Greatness of Arthur Ashe

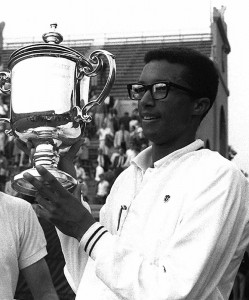

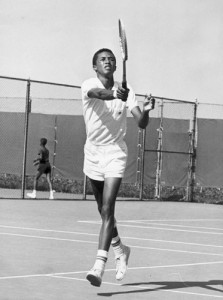

In 1968 Arthur Ashe won the U.S. Open and became the first African American to hold the number one ranking in men's tennis.

(On the 41st anniversary of him becoming the first African American to hold the number one ranking in men’s tennis, we remember and recognize the legacy of Arthur Ashe)

It is really a shame that so many people remember Arthur Ashe as “the black tennis player that died from AIDS.”

To say that the man was so much more would simply be an understatement.

Early Life

Most biographies of famous players always seem to start out with where the person was born, who their parents were, etc. That is in large part due to the significance of those facts in shaping a person’s life.

This article is no different.

Arthur Robert Ashe Jr. was born to Arthur Sr. and Mattie Ashe in 1943. The family lived in Richmond, Va., and Ashe’s father’s job as “Superintendent” provided him with a Caretaker’s Cottage in Brook Park, a “blacks only” area that coincidentally included tennis courts.

Arthur Jr. had been playing tennis for about a year when his mother passed away. Mattie had gone into the hospital for a simple surgery and contracted Toxemia—a form of blood poisoning—and died at the age of 27.

Ashe was just six years old.

A similar fate would befall Arthur, many years later.

Ashe was devastated by Mattie’s death. So much so that he could not bring himself to attend her funeral. He plunged himself into his school work and tennis, trying to alleviate the pain and burden of his mother’s passing.

About this same time, Ashe was introduced to the premier black tennis player in the country, a man by the name of Ronald Charity.

Ashe grew up playing tennis in his hometown of Richmond, Virginia.

With Charity’s coaching in tennis, Ashe’s father’s rearing in morality, and a black school system full of teachers that instructed Arthur to be better despite the inequities of the system, the groundwork was laid for an extraordinary human being.

In Ashe’s own words:

“Everyday we got the same message drummed into us, ‘Despite discrimination and lynch mobs,’ teachers told us, ‘some black folks have always managed to find a way to succeed. Okay, this may not be the best-equipped school; that just means you’re going to have to be a little bit better prepared than white kids and seize any opportunity that comes your way.’”

Finding Tennis

Ronald Charity recognized two things: Ashe’s extraordinary talent and drive, and his own limitations in developing that talent. So Charity passed the reigns to Dr. Walter Johnson, and extraordinary person himself.

Johnson was in a fact a medical doctor, and was the first black physician to be granted practice rights at Lynchburg General Hospital in Virginia in the early 1930s.

At the time of his introduction to Ashe, Johnson was already coaching Althea Gibson, the only African-American participating in world ranked tennis—that is until Ashe arrived.

Ashe continued to excel in his school studies, and his tennis prowess grew rapidly. The difficulty Ashe faced at that time was in finding quality opponents.

In those days, much of the country was still segregated, and Ashe was often times limited to playing only the black tennis players in the area. To find quality opponents, Ashe had to travel around the county.

He quickly started racking up tournament championships and national notoriety—Ashe was even featured in the Dec. 12, 1960, issue of Sports Illustrated feature, ‘Faces in the Crowd’.

This was to be the first of two such appearances for Ashe in Sports Illustrated, the second time coming in his second year at UCLA (he was also later named the SI Sportsman of the year and graced the cover of the Dec. 21, 1992 issue).

Shortly after the Sports Illustrated article, Ashe graduated first in his class from Maggie L. Walker High School in Richmond.

Impressed with both his academic and athletic accomplishments, UCLA offered Ashe a full ride scholarship to their school—a school with one of the best tennis programs in the country.

Becoming a Champion

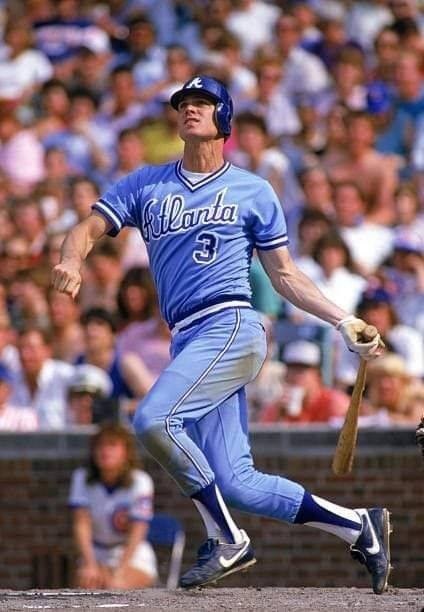

Ashe was named to the U.S. Davis Cup team in 1963 and later served as Captain.

In 1963, Ashe became the first African-American to be named to the U.S. Davis Cup team, a love affair that would last through 1970, and again in the years 1975, 1976, and 1978.

After his retirement from playing tennis, Ashe would captain the team from 1981-1985.

He won the individual NCAA Championship in 1965, and led UCLA to the NCAA team title the same year. He accomplished all of this while still managing to earn high marks in his studies and graduating with a degree in Business Administration in 1966.

Ashe spent the next two years serving in the U.S. Army. He was stationed at West Point, and played tennis for many of his assignments.

One of those assignments was the inaugural U.S. Open. (Although the event has a long and storied history, this was the first year it was known as the “U.S. Open.”)

Ashe won the event, but because of his amateur status received no prize money. That money was awarded to the runner-up, Tom Okker.

Ashe was feted by his fellow troops when he returned to base and entered the chow hall to an unexpected standing ovation.

Ashe remains the only African-American male to have won the United States’ premier tennis tournament.

The second of Ashe’s Grand Slam Singles titles came in 1970, at the Australian Open. Ashe defeated Australian Dick Crealy in straight sets to earn another Grand Slam title. Ashe was the only non-Australian to appear in any of the singles finals.

Perhaps Ashe’s greatest triumph on the tennis court occurred at Wimbledon in 1975.

In 1975 Ashe celebrated his 32nd birthday by defeating Jimmy Connors to win the Wimbledon Championship.

The defending champion, one Jimmy Connors, had blasted his way to the finals, manhandling everybody in his way. No one gave Ashe a snowball’s chance in hell of winning.

To make matters even more interesting, Connors had just announced a slander suit against Ashe on the eve of the tournament; Connors had already filed similar suits against the Association of Tennis Players, of which Ashe was a founder and current president.

The suits stemmed from remarks Ashe made about Connors’ non-willingness to play on the U.S. Davis Cup team and instead play at other events for prize money.

Ashe took the court wearing his red, white, and blue, Davis cup jacket.

In the first all-American Men’s Single final since 1947; in a stunning upset, Ashe defeated the heavily favored Connors, 6-1, 6-1, 5-7, 6-4, for Ashe’s third Slam triumph, and in the process laid the blueprint for how to defeat the powerful Connor’s.

Connors managed to win the first game, but it was all Ashe after that. Using “junk” to defeat him, Ashe took 12 of the next 13 games to take full control of the encounter. In the aftermath, Ashe took a not-so-subtle swipe at his vanquished, bitter foe:

“He hardly ever put the ball beyond the baseline—that’s a sign of choking.”

In retrospect, Connors biggest mistake wasn’t suing Ashe. In Ashe’s eyes, Connors’ turning his back on his beloved Davis Cup was tantamount to treason.

The two would later come to some kind of accord as Connors would eventually acquiesce and play on the victorious Ashe led Davis Cup team in 1981, he would again join the team in 1984.

Enter Apartheid

You have to go back to 1969 to find the beginnings of Ashe’s contributions to civil rights. In that year, he was denied entrance into the white-governed (apartheid) South Africa for the South African Open. The country would continually deny his requests for a visa, until 1973.

Ashe, shown with Nelson Mandel, was an outspoken critic of Apartheid in South Africa.

Ashe would use his denial of admission into the country to get South Africa removed from Davis Cup competition.

Ashe’s popularity, and his stance on Apartheid, made him a perfect fit for the U.S. State Department’s Goodwill Ambassador to Africa. Ashe was sent to several African countries to visit with heads of states, students, and vocal leaders.

It was during one such visit in Cameroon that Ashe discovered the only other black male player to win a Grand Slam event. Ashe sent the young man to France for instruction under the French Tennis Association, and Yannick Noah would go on to win the Men’s Single title at the French Open in 1983.

Finally allowed into the country, he became the first black to play in the Men’s Singles finals of the SAO, he also partnered with the man he defeated in the 1968 U.S. Open, Tom Okker, to win the Men’s Doubles title.

However, his struggle against Apartheid was far from over.

Ashe took part in countless protests and demonstrations against the South African government. In 1985, he was arrested outside the South African Embassy in Washington, D.C., for his part in an anti-Apartheid protest.

After a 22-year battle, Ashe and countless others were rewarded for their efforts. He, along with a very large delegation of other Americans, journeyed to South Africa to personally witness the repeal of Apartheid in 1991.

When Nelson Mandela was finally released from prison after 27 years, he was asked who he would like to meet from the U.S. His answer?—“How about Arthur Ashe?”

The Historian, Educator, and Author

When Ashe was about to enroll in UCLA, his original intention was to major in engineering or architecture, two very demanding fields of study. But he instead settled on the less demanding degree in Business Administration in order to devote more time to his tennis game.

As intelligent as Ashe was, and although he surely would have excelled in either field, he never returned to school to pursue those interests.

He did, however, return as an educator.

In 1983, Ashe took a position with Florida Memorial College to teach a course entitled, “The Black Athlete in Contemporary Society.” Much to his dismay, Ashe could not find a current and viable resource to instruct his class.

Embarking on a six year journey and leading a seven person team, the results of Ashe’s efforts culminated in the three volume set, “A Hard Road to Glory” a tribute to the triumphs and difficulties black athletes have faced and had to overcome.

Ashe also founded the African American Athletic Association, whose mission statement is as follows:

“Acknowledge the contribution, evolution, and success of African American culture to the history of world sports. Encourage racial harmony, respect, self-esteem, universal acceptance and appreciation for all people. Establish services and facilities to guide and support all athletes throughout their youth, amateur, professional and retired careers. Provide role models and mentors for community service learning, work-study and internship.

Administer financial support to the following categories of athletes with verifiable needs:” (various organizations cited)

Tragedy Strikes

Ashe suffered a heart attack in 1979. He would later undergo surgery for quadruple bypass, but continued to suffer chest pain. This forced him to retire from tennis with a record of 818-260, including his three Grand Slams.

He remains the only African-American male to have won any of these Men’s Single titles.

Even after being diagnosed with AIDS, Ashe continued to be a champion for Human Rights.

Ashe would have to under go a second bypass surgery in 1983. During this operation he received a blood transfusion: the blood Ashe received was infected with human immunodeficiency virus—HIV.

In 1988, this discovery was made. Ashe felt numbness in his hands, and when he sought medical attention, it was discovered the he suffered from what is known as toxoplasmosis, a condition most often found in people with AIDS.

The condition was kept private until 1992, when Ashe announced to the world, he had AIDS.

When asked if having AIDS was the toughest challenge he had ever had to face, Ashe replied:

“No, the hardest thing I’ve ever had to deal with was being a black man in this society…having to live as a minority in America. Even now it feels like an extra weight tied around me.”

In typical Arthur Ashe fashion, in the last months of his life, he founded The Arthur Ashe Foundation for the Defeat of AIDS, as well as the Arthur Ashe Institute for Urban Health, an organization designed to improve health care in inner city areas. Ashe would also find the time to write his memoirs, and speak to countless organizations on Aids awareness.

On World AIDS Day he made an appearance before the United Nations General Assembly to implore them to increase AIDS funding and to develop their understanding of the disease and its effects.

His tenacity in the waning days of his life prompted one time rival Jimmy Connors to remark: “He was out doing things, making his point, and taking care of business, right up until the end. I guess the sums up everything he stood for.”

On Feb. 6, 1993, at the age of 49, Arthur Ashe died of AIDS-related complications.

Former United Nations Ambassador Andrew Young, who had presided over the marriage of Ashe and wife Jeanne Moutoussamy back in 1977, delivered the eulogy.

Their daughter, Camera, in an almost cruel twist of irony, was six years old at the time.

In his memoir, “Days of Grace,” Ashe wrote:

“I do not like being the personification of a problem, much less a problem involving a killer disease, but I know I must seize these opportunities to spread the word.”