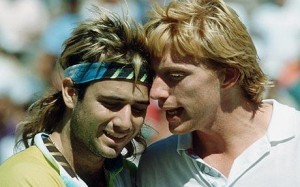

Agassi vs. Becker: The Rivalry That Could’ve Been

If it weren’t for Pete Sampras, Andre Agassi and Boris Becker could’ve had quite the rivalry.

Both men tried to be rivals to Sampras, but rather unsuccessfully. Becker’s game matched up poorly with The Pistol’s, who had all of the German’s strengths plus better movement. The only truly real classic matchup between Becker and Sampras was the 1996 ATP Tour World Championships in Hannover, where Sampras weathered Becker’s hot streak and crowd support before taking a five-set victory.

Agassi’s game, with its immaculate returns, made for a fun contrast with Sampras, but he couldn’t match The Pistol’s dedication and often responded to losses from his compatriot by going into deep dry spells.

Sampras therefore won a combined 32 matches against these two and lost 21. He defeated Becker in all three of their Grand Slam meetings, and Agassi in six of nine. He finished with as many majors as Boom-Boom (6) and Double-A (8) put together.

Agassi and Becker, though, could have provided an ideal contrast to one another as players. Both were men of charisma with loyal fan bases, though Becker’s serve and net-rushing approach was mostly favored by classicists, while Agassi’s enormous groundstrokes and flashy wardrobe appealed to younger fans.

Throw in the fact that they had very little use for one another, and they could’ve had the most interesting – and most contentious – rivalry since McEnroe-Lendl, if not McEnroe-Connors.

But this never came to pass. One reason for that was the age gap: Becker peaked in 1989, winning his third Wimbledon and only US Open, while also leading his nation to the Davis Cup crown. Agassi didn’t win his first major until 1992 and didn’t get to No. 1 until ’95.

Both men also suffered from droughts in the early part of the decade, as Agassi struggled with the game he’d been forced into against his will and Becker’s motivation wavered following the 1991 Wimbledon finals loss to Michael Stich.

Neither man was a consistent presence in finals weekend in those days, and when they did actually meet, the record was one-sided. Becker won their first three meetings, before Agassi ran off a streak of eight wins in a row. One reason for this was tactical, as Becker, in a misguided attempt to show his variety, often attempted to rally with the American from the backcourt.

In the 1990 US Open semis, for example, Becker rolled his serve in and stayed back, only coming to net or going for big serves on big points. It worked … for about set, before Agassi dismantled him 6-7, 6-3, 6-2, 6-3 and reached his first major final.

In the years to come this trend continued, as Becker appeared unsure of how to cope with Agassi’s passing shots and brutal ball-striking. Agassi also recognized a subconscious tic of Becker’s – sticking out his tongue in the direction opposite of where he planned to serve – that made his massive serving easier to handle.

Even when Becker came into their matchups playing well, such as the 1994 Miami event, Agassi seemed to approach the match knowing what Becker would do, and knowing how to counter it.

As a result, they had relatively few classic encounters; going into 1995, the only matches between them that fit that description would be the 1989 Davis Cup semis, where Becker overcame a two-set deficit to beat the American in front of the German crowd, and the 1992 Wimbledon, where Agassi won in five sets on his way to his first major title.

So, going into their 1995 Wimbledon semi, Agassi was the heavy favorite. At this point he was not just dominating Becker, but the rest of the tour, as the world’s top-ranked player and holder of the US Open and Australian Open titles. He had dropped just one set in the tournament to hard-serving David Wheaton, while Becker had struggled, dropping sets against unheralded Jan Apell and Jan Siemerink, and barely avoiding ouster at the hands of Cedric Pioline.

The match began as expected, with Agassi catching the ball almost as soon as it bounced and flicking it seemingly anywhere on the court he desired, keeping his big opponent on the defensive and unable to take charge of play. Agassi easily won the first set, 6-2, and led 4-1 in the second, up two breaks.

As easy as the match had been up to that point, it was perhaps understandable that his play dipped for a moment, giving back one of the breaks he’d taken from Becker. Harder to anticipate was the effect that this momentary lapse would have on the play of both men.

Shown just a crack of light, Becker played like a man reborn, serving huge and charging the net with confidence. He still knew better than to try and out-rally Agassi, so he chipped his backhand low and deep, forcing the American to make his own pace (much like Feliciano Lopez recently did to Rafael Nadal at Queens). Rather than another opponent, this made Becker into a kind of heavy punching bag that Agassi had to keep throwing haymakers at, even though it would still be there long after his arms grew tired.

And if Agassi didn’t swing as hard as he could, risking exhaustion and error, the ball would land short, giving Becker an invitation to come to net.

From down 4-1, Becker charged back to win set two in a tiebreak, then won the third 6-4. In the third set Agassi managed to take care of his own service games, but later said that Becker’s comeback had rattled him, and kept him from maintaining his focus. In an inspired fourth-set tiebreak in which his serve was untouchable and he hit an amazing forehand return winner, Becker prevailed 7-1, taking the match and reaching the finals.

And here’s where things really could have gotten interesting. Agassi was all smiles as he greeted Becker at net, congratulating him on his performance, but the look on Becker’s face suggested that he had little patience for his opponent in the high-top Nikes and pirate rag.

In a subsequent press conference, Becker said that Agassi was arrogant, unpopular with the rest of the tour, and had been promoted at the expense of other players.

Agassi, egged on by coach Brad Gilbert – who had upset the German several times as a pro and disdained the German’s pretentiousness – turned the North American hard court season of 1995 into a summer-long revenge fantasy, winning every US Open warmup event in anticipation of rematch with Becker.

They got it in the USO semis, where Agassi narrowly overcame the German in four tight sets.

It looked like the beginnings of a series of grudge matches, but this never came to pass. Both men had private issues to deal with – issues that were brought to light by Pete Sampras. Agassi lost the US Open final to The Pistol and spent years dealing with the disappointment, eventually spiraling to No. 141 in the world, dabbling with crystal meth use and thoughts of retirement.

He would eventually recover, but by the time he got back to the summit of the game in 1999, Becker was done as a top-flight player. He had lost the 1995 Wimbledon finals to Sampras, then in 1997 was ushered off the lawns again by The Pistol. In both of those four-set encounters, he had failed to break the Sampras serve even once, and his pride would not allow him to contend for titles that were out of his reach.

He hung around the smaller events, but stopped playing the majors after the ’97 Wimbledon. He and Agassi met one final time in the 1999 Hong Kong finals, with the American prevailing in a tight three-set final. By then, though, their careers were headed in opposite directions. Agassi’s life was permanently changing, starting with he and wife Brooke Shields filing for divorce that very week. Within months, he’d be winning the Roland Garros and US Open titles and returning to No. 1.

Becker chose to play Wimbledon one more time that year, eventually being outclassed by Patrick Rafter, then never playing on the ATP Tour again. And so the chances of additional heated clashes between them died.

At least on the tennis court. When Agassi’s memoir, Open, revealed his dabbling with meth use and subsequent lying to escape suspension, Becker publicly announced his befuddlement with the American’s behavior, said he was hurting the game and openly wonder if some of his GS losses to Double-A might not have taken place under fair conditions. But, despite these disagreements and allegations, he insisted that he really liked Agassi. Really.

The volleys Agassi fired at Boom-Boom contained no such diplomacy. His book described Becker as “this f–king German,” accused him of trying to break the American’s concentration by blowing kisses at Shields during the ’95 USO semi, and voiced regret that his final loss on tour came to the similarly named Benjamin Becker of Germany.

Guess some old wounds don’t heal. But they might at least get therapy should these two meet on the seniors’ tour.

Jim Courier, are you listening?