Why Roger Federer’s “Arrogance” Isn’t

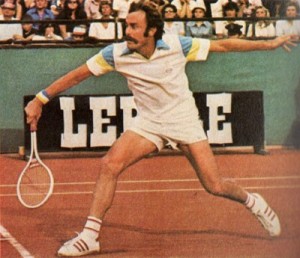

Following a clay court exhibition match against Bjorn Borg in 1978, John Newcombe was asked his opinion on how he would match up with the Swede on grass. He proceeded to explain why he, no matter the surface, enjoyed playing against the man from Stockholm.

“I don’t feel he’s got anything that can really hurt me,” the Australian great said.

At this point in his career, Borg was already a two-time champion at Roland Garros and had also twice lifted the cup at Wimbledon. He was, essentially, the best player in the world. What’s more, Newcombe’s comments came after a 6-2, 6-4 loss to the Swede.

Newcombe, in his next sentence, said that this didn’t mean that he would be able to beat Borg, who played the counterpuncher’s game better than any tennis player ever has. What he meant was that he was he, as an attacking net rusher, would be setting the tone of the point more frequently than the Swede.

Borg might be able to pass him, might be able to lob over his head, might be able to keep chasing balls till Newcombe missed – the Aussie still could and would play the game plan he liked, even in losing.

Still, had there been internet message boards in those days, the “really hurt me” sentence would almost certainly have shown up online with no context attached to show that John Newcombe was either arrogant, disconnected from reality, or both. Tennis has a long history of players who say exactly what they think at the time, and fans online still have yet to grasp that.

In “The String Theory,” David Foster Wallace posed the thesis that tennis players tend to winnow out much of the vagaries of life. They live in a world of nonstop practice, travel, and competition against hundreds of different players, all of whom can consistently drill minute targets on the opposite side of the court while on the dead run.

If they can only hit that bull’s eye 95 times out of a hundred and the other guy can nail it 96 times, they may leave the tournament with empty pockets; they therefor have little time to explore nuances. Wallace arrived at this theory by listening to Michael Joyce, a journeyman player who would never be ranked higher than No. 64, say that an opponent he met in qualifying had a big serve, but “didn’t belong on a pro court.”

Wallace wrote at the time: “Joyce didn’t mean this in an unkind way. Nor did he mean it in a kind way. It turns out what Michael Joyce says rarely has any kind of spin or slant on it; he mostly just reports what he sees, rather like a camera.”

This extends beyond unknown players who are fighting to make a living, though. Get into the top 10, and you see players battling for their pride. Get to the very summit of the game, and there are players trying to carve out their niche in history, and affect how they will be spoken of by future generations.

Pete Sampras was a good example of this. The Pistol has been known since his days at the top of the tour as a quiet person, but when he has spoken there has been very little doubt about what he means. On his blowout victory over Yevgeny Kafelnikov in the 1997 World Tour Championships: “When my game clicks like that, I’m unbeatable.”

On the difference between him and Patrick Rafter circa 1998: “Ten grand slams.”

On why Tim Henman (one of Sampras’ best friends on the tour) was never able break through and please his British fans at Wimbledon: “I did everything better than Tim.”

Devoid of context, these statements sound more than a little arrogant. In fact, context included, they may still meet the literal definition of the term. In Sampras’ defense, though, he wasn’t trying to be arrogant any more than he was trying to be diplomatic; he just stated what he saw.

Furthermore, his blunt honesty extended beyond statements burnishing his own record. He had no troubled expressing his astonishment when the service returns of youths Marat Safin and Lleyton Hewitt in the ’00 and ’01 US Open finals took him out of his game.

When Peter Bodo at Tennis.com once mentioned that Sampras, whose clay court results lagged far behind his achievements elsewhere, had won in Rome in 1994, Sampras replied: “That was a fast clay court.”

One of the first hints of Roger Federer’s self-image came in 2005, when Andre Agassi set up a quarterfinal clash with him at the Australian Open. Federer had, in the previous year, become the first player since Mats Wilander in 1988 to win three major titles in one year. Asked if he needed to up his standard of play against the 30-something American legend, he replied: “I think he has to raise his game, not me.”

Over the years The Great Swiss’ reputation as a player has grown and grown: He has broken Sampras’ record for Grand Slam titles, holds the all-time mark for consecutive weeks spent at No. 1, and only recently saw his unprecedented streak of 23 Grand Slam semis broken.

All the while, he’s been reputed for decency, winning the Stefan Edberg Sportsmanship Award six times running. James Blake, following a thrashing at Federer’s hands at the 2006 Indian Wells told the crowd after the match that, during his hospitalization in 2004 following freak accident that broke his neck, the only card he received from his contemporaries on the tour came from the Swiss.

Andy Roddick, who has lost four Grand Slam finals to Federer, once told the Swiss: “I’d love to hate you, but you’re really nice.”

Nice he may be, but is he humble? That depends on your definition of the word. The man who cried when Rod Laver presented him the 2006 Australian Open trophy and seemed genuinely surprised when Agassi said Federer was the best he’d ever played has not rushed to proclaim his own greatness. He is, however, a competitor, and knows that sometimes the battle starts before you reach the battlefield.

And so he stated that Rafael Nadal’s game was “one-dimensional” even as he was struggling to solve him in 2006. He expressed puzzlement over the rush to proclaim Andy Murray the Wimbledon favorite at the 2009 AO. This year, he implied that clay, his worst surface, did not reward an all-around game.

I read the article where he made these comments. I also listened, prior to the AO final this year, when he said that Murray would face more pressure than he would because the Scot hadn’t won one yet and because, he jested, no British player had won a major in “150,000 years.”

I cringed both times, not because I was offended, but because I knew that somebody out there, such Yahoo! Sports blogger Chris Chase (who pays a lot more attention to scandal than actual tennis) was going to try and turn them into an issue. Why? Because some people need controversy; the sport isn’t interesting enough by itself.

Would I have used the words Federer has at times regarding Murray and Nadal? Probably not, but then again, I write and edit for a living; words are my profession, while Federer’s is tennis.

In just a few days the crown jewel of the tennis season will begin. We will probably see a lot of tennis, followed by a lot of press conferences which will contain a lot of words. Many players will say things that seem unnecessarily forthright; Nadal will probably say things that seem unrealistically complementary. That’s his style, and that’s how his uncle taught him to behave.

We can parse their words, knowing full well that they are not professional wordsmiths and that they will eventually disappoint us.

Or, we can just enjoy the tennis.