Don Larsen’s Perfect Game: My Uncle’s Tall Tale

On October 8, 1956, New York Yankees pitcher Don Larsen arrived in the clubhouse, and much to his alleged surprise, found a baseball tucked into one of his shined cleats. Placed there by pitching coach Jim Turner, the ball was the signal that Larsen would be the starting pitcher that afternoon–game five of the World Series.

What happened next was one of those magical moments in sports when the near-impossible, the utterly implausible is dragged into reality through little more than sheer force of will. Larsen set down 27 Brooklyn Dodgers in a row, and recorded the first perfect game and the first no-hitter in postseason history. His was the only such feat ever accomplished until 53 years and 363 days later, when Philadelphia Phillies ace Roy “Doc” Halladay no-hit the Cincinnati Reds in game one of the National League Divisional Series with an epic one-walk performance during a 4-0 win.

In the spirit of remembrance, I thought I would share with you a piece of family lore that concerns Larsen’s perfecto; but first, a little more background.

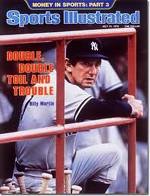

Interestingly enough, when Phillies skipper Charlie Manuel was a player, the only two managers he ever played for were Billy Martin (Min 69-72) and Walter Alston (LAD 74, 75), both of whom were present for Larsen’s perfect game. Alston, of course, as the Brooklyn Dodgers manager, and Martin as the Yankees starting second baseman that afternoon.

Larsen maintains to this day that he had no idea he was to start game five. The claim is a bit dubious simply because he was listed as the starter in most national newspapers that day, but former Yankee teammates like Bill “Moose” Skowron have backed his assertion.

“I still can’t believe the look he had on his face when he saw the ball,” said Skowron, “… shock or something.”

Larsen had performed poorly in game 2, lasting less than two innings and surrendering four runs on four walks, but his control didn’t desert him that way in game five. Larsen needed just 97 pitches to complete his perfect game, a supremely economical performance.

“I had great control,” recalls Larsen, “I never had that kind of control in my life.”

“His stuff was good, good, good,” agreed hall of fame catcher Yogi Berra. “Anything I put down he put over.”

There were several close plays in the contest, and Larsen surely benefitted from luck to some extent, as must any pitcher who throws a perfect game.

In the second inning, Dodger second baseman Jackie Robinson swatted a line-drive that bounced off Yankee third baseman Andy Carey’s glove, but as luck would have it, bounced directly to Gil McDougald, who threw out Robinson on a close play at first. In the fifth inning, legendary outfielder Mickey Mantle made a one-handed catch in left-center to steal a sure extra base hit away from Dodger first baseman Gil Hodges. The next batter, Sandy Amoros, a young outfielder with loads of athletic ability, hit a long ball to right that went foul. When he was asked about the play later, umpire Ed Runge held up his thumb and index finger and said, “That much.”

As the game went on, the atmosphere became increasingly tense in Yankee Stadium, and Larsen’s teammates remained silent as baseball custom demands while a no-hitter is in progress. Larsen himself appears to have been unconcerned about the superstition, and may have mentioned the perfect game bid in the dugout to his teammates. Legendary broadcaster Vin Scully perfectly captured the mood in the stadium when he said in the beginning of the ninth: “Yankee Stadium is shivering to its concrete foundations.”

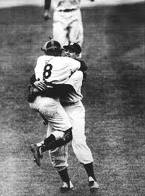

With two outs in the ninth, and Dodgers pinch hitter Dale Mitchell in a 1-2 hole, Larsen caught Mitchell looking for the 27th out and walked off the mound into the arms of Berra and history.

It was a performance that shook the baseball world, Larsen was a hero, and the Yankees went on to win the series.

Bird and Gooney Bird

The family lore I alluded to previously concerns a yarn sometimes spun at family functions by my uncle Pieter. It concerns Larsen and what actually happened the night prior to his perfect game. Legend has it that he showed up drunk to the ballpark that day, though several people who were with him that night refute this claim.

My uncle tells a different story, and though it can’t be properly verified, it is worth recalling.

My uncle claim’s to have been present at Toots Shor’s famous restaurant at 51 West 51st Street in Manhattan that night, when Larsen and the Richman brothers, Milton and Arthur, newspaper friend’s of Larsen’s, came in for dinner and a few drinks. Somehow, my uncle ended up at the table with Larsen and company, and the booze began to flow quite liberally. My uncle was a tremendous jazz fan, and at least one member of Larsen’s entourage was as well, and the conversation soon turned to the merits of the recently deceased jazzman Charlie Parker. Before long, the discussion had attracted a dark haired young man with penetrating eyes. My uncle being the friendly sort, tried to engage the man in the dialogue.

“You a fan of Bird too son?” He asked the man.

“I like too many things and get all confused and hung-up running from one falling star to another till I drop,” nodded the man. “This is the night, what it does to you. I had nothing to offer anybody except my own confusion.”

“What the hell did he just say?” Asked Larsen, with a confused look on his face.

“I don’t know,” my uncle said. “I couldn’t make heads or tails of it, sure sounded good though.”

“What’s your name, son?” asked my uncle, proferring a hand.

“Jack,” he replied, accepting the offered hand. “Jack from Lowell, Massachusetts.”

“Well, Jack,” asked Larsen with suspicion. “What’s your take on old Yardbird?”

“Great things are not accomplished by those who yield to trends and fads and popular opinion,” said Jack. “My witness is the empty sky.”

My uncle says that with this, the dinner guests all just looked at one another. They were not accustomed to the strange ways of their new friend, and his manner of speaking made them all a bit nervous.

What happened next, according to my uncle, was one of the great moments in history that will never be regarded as fact. He swears he saw it, but no else has ever spoken of it, nor is likely to in the future.

Larsen asked our new guest what he thought of the Yankees win the day before, in game four of the series, as our new friend had professed to be a huge baseball fan, and relayed a story to us for unknown reasons about how he devised an entire imaginary league for fun. In any case, this is what he told Larsen:

“A pain stabbed my heart as it did every time I saw a girl I loved who was going the opposite direction in this too-big world.”

“Oh, so you are a Dodger fan,” said a suddenly tense Larsen. “I hate your kind, get away from this table at once!”

“All our best men are laughed at in this nightmare land,” said Jack with a wry smile.

“Offer them what they secretly want and they of course immediately become panic-stricken.”

“I’m sick of this guy,” cried Larsen to my uncle. “Why is he even here? Why isn’t he in Brooklyn with the rest of the bums, or better yet, back in Massachusetts?”

“He told me he followed a bunch of friends down here,” my uncle said. “He’s passing through.”

“He said they were all sitting in Lowell …” started my uncle, before he was cut off by Jack’s frantic gesticulations and suddenly feverish speech.

“…But then they danced down the street like dingledodies,” said Jack, “And I shambled after as I’ve been doing all my life after people who interest me, because the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn, like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes “Awww!”

That was all that Larsen could stomach, not being the poetic type, and lunged at Jack and a melee ensued. Larsen, my uncle and the Richman brothers ended up fighting half of the bar, though Jack somehow disappeared. After making their escape, my uncle and the rest returned to Milt Richman’s car to drive back to the hotel, when they spotted a note tucked into the windshield wiper.

“Our battered suitcases were piled on the sidewalk again; we had longer ways to go. But no matter, the road is life.”

“Love Jack.”

They returned Larsen to the hotel and my uncle took his leave of the rest. It wasn’t until several years later, after he had become quite famous, that my uncle realized that the young man who had so irritated Larsen was none other than Jack Kerouac. Ti-Jean himself.

Larsen, for his part, refuses to speak of this incident to this day, and my uncle contends that he threw the perfect game out of spite. In any case, that’s my uncle’s story and I am sticking to it. Don Larsen remained a fan of Charlie Parker, and has never read any of Kerouac’s books. My uncle has been “hospitalized” for years now, but has always stuck to his guns regarding what happened at Toots Shor’s that night.

Call me crazy, but I believe him.