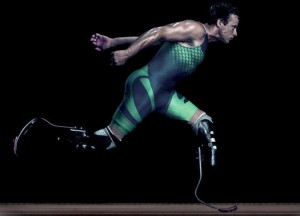

“The Blade Runner” One Step Closer to Olympic Dream

Try to wrap your brain around this scene:

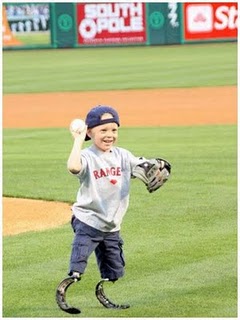

An 11-month-old South African baby lies in a post-op recovery room, having just had both legs amputated just below the knees.

As his parents hover over the boy, they put aside their own doubts and fears to bravely speak words of affirmation and hope.

Yet secretly, in private moments, they wonder how their child will ever cope in a world populated by people with legs, ankles and feet.

As is true in much of life, the outward appearance often speaks the loudest while hidden inside, the attributes of courage, heart and determination quietly do their work and ultimately have the last word.

Oscar Pistorius was born without fibulae (lower leg bones). His deformed lower legs were surgically removed before he was a year old. He was fitted with carbon fiber prostheses which emulate the function of leg bones, ankles and feet.

In time, the boy with no legs became actively involved in rugby, water polo and tennis. In 2004, he took up running as a therapeutic recovery exercise following a rugby injury.

Before long he was dominating every Paralympics race he entered, from 100m through 400m. Eventually he became the world record holder in the “disabled” version of the 100m, 200m and 400m sprints.

In Beijing, 2008, he won sprinting’s Olympic triple crown (100m, 200m, 400m).

The “disabled” version.

Some would say his accomplishments represented the peak of his potential. But Oscar knew other, more able-bodied runners were producing faster times—and he wanted to run with the big dogs.

He even had visions of one day running beside the world’s best in the World Championships and especially in the Olympics.

When it was discovered that Pistorius could run the 400m in the 46-second range, against able-bodied opponents, the cries of “unfair advantage” began to arise. Track and field’s governing body (IAAF) sponsored some tests and concluded that the South African’s artificial limbs did indeed provide a more energy-efficient assist.

Pistorius was banned from sanctioned competition against able-bodied opponents.

Pistorius viewed the ban as just another obstacle to overcome. He fought the ruling, arguing that contrary to having an advantage, his body lacked any muscle mass or blood volume below the knees.

An arbitrary panel heard the case and ruled that the ban was based on inconclusive evidence. The ban was overturned.

Pistorius meanwhile had gradually bettered his time to a respectable 45.61—still not quite good enough to qualify for the Olympics on time alone. Since he was only the fourth fastest 400m runner in South Africa, his chances of being selected for any major global championships were nil.

His one and only shot at either this year’s World Championships in Daegu or the 2012 London Olympics was to meet the qualifying standard time of 45.25. In a series of races this year, he was often relegated to run in the lowly-esteemed lane one. Even then, his very presence in the races seemed almost an afterthought.

All his chances came and went this summer without Pistorius having hit that magic 45.25 standard—save one final meet last Tuesday in Lignano, Italy.

Pistorius, running in a low-profile race, against a field hardly capable of pushing him to record times, found another gear. He demolished the Olympic standard, winning easily in 45.07—and running in lane three for a change!

Not only did Pistorius get the automatic qualifier, he moved up to No. 2 on South Africa’s 400m list.

Of course, to fulfill his goal of medaling at the World Championships or Olympics, Pistorius will have to scale another wall. He must first be selected by his country, then move through the preliminary rounds and qualify for the finals.

That will be another day, another challenge. Last Tuesday he earned his ticket.

But even with all Oscar has accomplished so far—perhaps because of how much he’s accomplished—the scene of Pistorius lining up in the 400m finals in Daegu or London is one I think we’re all having a hard time wrapping our brain around.