Role of High Schools and Clubs in the Development of Future WPS Players

With the draft process for the 2010 United States (U.S.) Women’s Professional Soccer (WPS) in full swing and teams

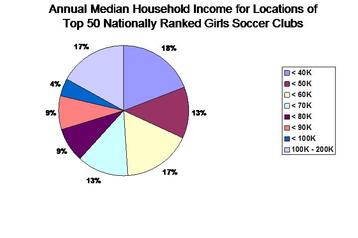

Median Income of Top Ranked Girls Soccer Clubs

rushing to recruit international players, it is important to reflect on why coaches prefer foreign players over home grown talent.

Given the success of international players relative to the U.S. players in the inaugural WPS season, it is not surprising to see this trend. WPS league statistics for 2009 show that leaders in goals scored, assists, minimum number of goals given by a keeper, and number of shutouts by a keeper are all foreign players.

Granted the U.S. players enjoyed a dominant phase on the international scene for over two decades. That dominance, however, is slowly waning; other countries are catching up to the U.S. and are developing quality players.

One of the models that other countries are using to develop female soccer players is through youth academies associated with men’s and women’s teams of their professional leagues, in addition to local clubs.

The model in the U.S. is different.

The U.S. develops soccer players through its club system and the state Olympic Development Program (ODP), and collegiate soccer.

The problem is these clubs and ODP are not accessible to everyone. And public high schools do not partake in developing soccer players.

Soccer players playing in the club system and ODP are referred to as “elite”. They are the chosen ones who, in the view of coaches selecting them, have the ability to play at the next level.

Is the level of play really at the next level? Are talented players from every corner being tapped?

It costs an average of $1000 or higher per player per year to play for these clubs. To be in an ODP system, it can cost another $800 – $1500. These costs do not include travel, lodging, and miscellaneous expenses a player incurs.

Looking at the top 50 nationally ranked clubs (e.g., U16 girls), it quickly becomes evident that nearly 70% of the top 50 soccer clubs in the U.S. are located in areas where median household income is above national average (~$50,000). Most of these clubs are located in suburban areas where affordability is not an issue.

There is little doubt that these clubs are not within the reach of low income groups and rural areas. Talented athletes in these regions are perhaps drawn to other relatively affordable sports like basketball. No one can dispute the fact that quality of play in women’s basketball at collegiate level or professional level is way higher than soccer.

On average, a D1 women’s basketball team draws fans in tens of thousands whereas a D1 women’s soccer team draws fans only in hundreds to few thousands.

Again, the question is why are talented athletes not drawn to soccer?

High schools muddy the situation further. Soccer programs at most public high schools do not show any promise.

Only two sports get top attention at public high schools: football and basketball. Some schools extend the attention to Lacrosse. Schools make every attempt to hire good coaches for these sports.

Emphasis for quality coaching is not present for soccer.

There is absolutely no development of players at the high school level. They expect players to be already developed. In fact, high school system and club system are at odds.

The style of soccer played at high schools is very regressive and counter productive for development. Because of the poor coaching and quality of soccer at high schools, some club coaches even go to the extent of discouraging their players from playing high school soccer. This is an emerging trend.

Again, because of disparity in prior training, the same players who excel at club level excel at high schools.

Players who do not have the luxury of playing for a club or ODP are left with no other option but to play for high schools and if schools are not supportive of soccer, they are at a disadvantage.

Programs such as ODP are out of reach for these players. If a player is not playing club soccer, chances are that player has not even heard of ODP. State soccer associations do not have any relationship with high schools to make the program more visible.

High school soccer, to a certain degree, operates in a vacuum. It has become totally irrelevant because college recruiting happens at the club level as well.

Contrary to this, sports like football and basketball that are prominent at high schools are able to churn out great athletes. Players get recruited for college based on high school performance and not at any club play.

Why can’t soccer adapt the same model?

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 calls for equal opportunities for women in academics and sports at federally funded institutions. In sports, players are expected to be given access to quality coaching and competitive facilities.

Yet, sports like soccer are not regarded highly by school systems.

Most schools hire teachers who never played soccer or who have little soccer experience to coach soccer teams.

The situation obviously cannot be corrected overnight. It may take a long time and experiments with different models to find a solution. Schools struggling for educational funds may not be willing to allocate resources and efforts to improve their sports programs. Unlike football or basketball, soccer at all levels in the U.S. is not a revenue generator.

Several different approaches can be tried to improve the quality of youth soccer in the U.S for both boys and girls.

State soccer associations can attempt to decentralize the ODP program and introduce county level development programs. Some states such as Maryland attempted this but for some unknown reason the program has been disbanded.

These county level developmental programs should be low-cost programs that are open to everyone with no selection process to weed out some players.

These programs should begin at a U9 or U10 level.

State soccer associations should run these programs and enter into partnerships with county elementary and middle schools to promote these programs. Once players are in this system, irrespective of their involvement in club level, they should be encouraged to tryout for state level ODP teams with full access to need-base scholarships. Even if players do not follow ODP, they will be prepared for high school soccer.

Soccer clubs can also enter into partnerships with local schools to promote soccer. Critical contributions from clubs could be at the coaching level.

Another approach could be to create youth academies tied to WPS teams. WPS teams can offer open tryouts and camps in their communities and recruit players who show promise to develop them in their youth academies. Some Major League Soccer (MLS) teams do have super Y teams for different age groups that compete in United Soccer League.

Finally, the ODP system itself can be revamped. Currently, ODP system is merely a stepping stool for players to be recruited by colleges. It is a ticket to a spot on a college team. Though the intention is to develop players, there is no high level technical and tactical training provided to ODP recruits. It merely provides the players an opportunity to compete at higher levels.

The goal of the ODP program in each state should be to make players coming in to leave as better players than they were at the time of recruitment. That metric is currently missing in the ODP system.

The alternatives suggested are some examples of how U.S. can develop future professional soccer players. A working paradigm can evolve over time by a combination of these approaches.

Picture Credit: Shobha Kondragunta. Data Source: http://www.city.data.com