All Hail The Kings

It’s been a strange year for sport. A team of Geriatrics made the NBA Finals, taking the defending champs to 7 games. Two teams who had never won a World Cup played for the championship. A team (avert your eyes, Bostonians) with a 3-games-to-zero playoff series lead melted and lost in Game 7 on home ice. At baseball’s all-star break, 3 teams who didn’t finish last year with a winning record lead their divisions. The once-unflappable Tiger Woods flapped and, ultimately, folded. A tennis match lasted over 11 hours, spanning 3 days. The Miami Heat built a basketball franchise that promises to be hated by all.

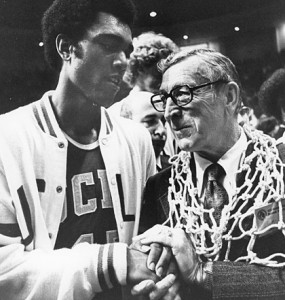

But when the year is over and Time Magazine writes its Person of the Year issue, these instances will all be asterisks, if that. Sport in 2010 will be marked neither by tragedy nor travesty, but rather by life running its course. Not 40 days after John Wooden – The Coach – passed away, so, too, did The Boss.

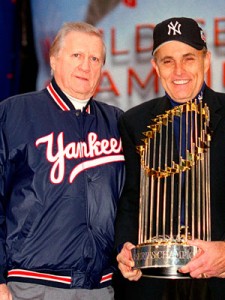

George Steinbrenner was, no doubt, a polarizing figure, but nowhere more than in the Bronx. What he represented drew the ire of eyes in Boston, Queens, Atlanta and Los Angeles, to be sure, but it wasn’t until twenty years into his ownership of the Yankees that his own fans warmed to him – and then, only after a three-year, league-imposed hiatus from the game.

But this is not a history lesson. No, this writer prefers to leave history to those more historically inclined. Steinbrenner’s passing happened at a fitting time; it was, after all, the one day of the year in which there is no sports news for ESPN or any other outlet to break. And, let it be known – even in the opinion of one who often criticizes ESPN for capitalizing on narcissistic moments in sport – that ESPN covered the passing of The Boss admirably, devoting an entire morning and early afternoon of coverage to Steinbrenner, his friends, once and former co-workers and the rest.

I am a Boston fan. I grew up in Upstate New York, with the exception some instances during my childhood in which I was transplanted in Massachusetts’ South Shore. That was enough to sell me on the Red Sox and Bruins and Celtics and Patriots, despite the fact that for most of the year I was surrounded by a majority of Yankees, Rangers, Knicks and Bills fans.

That does not make me immune to feeling the same chills that so many others probably felt this morning when Bob Knight, during a phone interview on SportsCenter, broke down crying not once, but twice while talking about Steinbrenner. Or when Dave Winfield got choked up on camera. I’m almost afraid to watch Derek Jeter’s interview, when it comes.

Baseball is the one sport whose season takes place without much competition. Sure, there is the occasional major golf or tennis tournament and every other summer, the World Cup or Olympics take center stage for a few weeks. But really, baseball goes from April to September without rival – it is only its postseason that is really challenged by other, regular sports. So to say that Steinbrenner was almost single-handedly responsible for making baseball what it is today might seem like an overstatement.

It’s not.

In 1993 – the year George Steinbrenner returned to baseball after being forcibly removed from it in 1990 – Bobby Bonilla was the highest paid MLB player. He made 6.2 million dollars that year. There were 272 players who made seven figures playing professional baseball that year, and the league average salary was $815,723. In 2006, the last year that Steinbrenner himself retained full control of the Yankees, the league average salary was $1,937,004 and 410 players made seven figures (or more) annually. It is no surprise that four of the highest five highest salaries belonged to players wearing pinstripes that year.

Inflation can account for that. So, too, can Steinbrenner’s willingness to pay whatever it takes to put the best team on the field. As a fan, it’s done strange things. Ticket prices have skyrocketed to help keep up with booming salaries, and if you stand around inside the gates of Fenway Park long enough, you’ll always see at least a few groups of people shrieking and dancing as soon as they enter the turnstiles – the ticket prices may have made them wait a year or two longer than they’d planned to get to their first game, but it has made the end of the journey that much more incredible. In a way, fans have become more attached to their teams because they can’t afford to spend as much time with them as they’d like to.

Absence, as they say, makes the heart grow fonder.

Steinbrenner’s passing occurred not 24 hours after another Yankee legend took his seat on the pearly pine. Bob Sheppard, for decades the voice – The Voice, indeed – of the Yankees, passed away yesterday. It is fitting, as ESPN’s Adam Schefter noted on Twitter earlier, that Sheppard is already upstairs to announce George’s arrival.

John Wooden and George Steinbrenner – both icons in their own right, two men who really couldn’t be more different in their approaches to the games they involved themselves with. Wooden used a chalkboard as his pulpit, halftime speeches were his homilies and practices – practice was a time for self-improvement and awareness of team. If you knew yourself, according to Wooden, you could function as a successful teammate. Coach preached love, faith and stuck to the Biblical passages he grew up on when looking for a way to teach his players. He was a teacher first, a coach second, and devoted through and through.

Steinbrenner won 7 World Series as an owner. Wooden won 7 straight NCAA championships. They did it in different ways.

Wooden’s high school sweetheart, Nell, became his wife. When she passed twenty-five years ago, he visited her grave and wrote her letters every month. Her picture rested beside Wooden’s pillow, along with those so many letters. He loved and was loyal to her to his last breath and beyond. Steinbrenner went through 17 managers in his first 17 years. Loyalty, it’s safe to say, ranked well beneath victory for him – this was the man, after all, who said that second to breathing, winning was the most important thing.

They were born barely 300 miles apart, and tonight, in Wooden’s town, they’ll talk about Steinbrenner’s death.

While they worked in different ways, they were both products of their devout mid-western upbringing. They both put victory first, but a different kind of victory. Wooden’s was moral. Steinbrenner’s was, well, in the standings. But to say that Steinbrenner stumbled upon his success couldn’t be more untrue. He worked hard for his money in his family’s shipbuilding business that thrived on the shores of Lake Erie, then used that money to buy the Yankees and implored his teams to work harder than he had. Wooden worked at basketball, at being morally sound and physically fit, and letting the rest sort itself out.

Both expected their players to succeed. Both, as it turns out, expected their players to remain well-groomed. Both, history will tell us, got what they wanted.

The game Wooden helped to so advance has changed. It has become a game for spotlights and superstars, one in which ability and fame promise a sort of societal freedom that can’t be found anywhere else. There are no more Bill Waltons or Lew Alcindors, just Kobe Bryants and, the newly minted super-heel, LeBron Jameses. Wooden would not approve of the recent goings-on in South Beach, but then, it’s safe to say that Wooden wouldn’t approve of South Beach to begin with.

The Miami Heat have learned from Steinbrenner’s model. But they have borrowed from Wooden, taking pay cuts to play with winners. Whether or not they employ those lessons to perfection is yet to be determined. If they do, they may be the first team to successfully bridge the gap between Wooden’s game and Steinbrenner’s approach.

That’s no matter. Tonight, even though they’re not playing, we’re all Yankee fans.

And how fitting, at day’s end, that the only game being played tonight is at Angel Stadium.